IAHSS Foundation

The International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety (IAHSS) Foundation was established to foster and promote the welfare of the public through education and research and the development of a healthcare security and safety body of knowledge. The IAHSS Foundation promotes and develops research to further the maintenance and improvement of healthcare security and safety management, and it develops and conducts educational programs for the public. For more information, please visit www.iahssf.org.

The IAHSS Foundation is completely dependent on the charitable donations of individuals, corporations and organizations. Please help us continue our mission and our support of the healthcare industry and the security and safety professionals who serve institutions, staff and, most importantly, patients. To donate or to learn more about the IAHSS Foundation, please visit the website or contact Nancy Felesena at (888) 353-0990.

Thank you for your continued support.

Ronald Hawkins

Research Committee Chair

IAHSS Foundation

IAHSS Foundation Board of Directors

Bill Navejar

President

Ashley Ditta, CHPA

Treasurer

Bonnie Michelman, CHPA, CPP

Massachusetts General Hospital

Steve Nibbelink, CHPA, CA-AM

Secure Care Products

Brigid Roberson, Ed.D., CHPA

Texas Medical Center

Chad Rioux, CHPA, CPP

Motorola Solutions

Paul Greenwood, CHPA

Unity Health Toronto

Scott Hill, Ed.D., CHPA, CPP

King’s Daughters Health System

Marilyn Hollier, CHPA, CPP

Security Risk Management Consultants

Ronald Hawkins

Security Industry Association

Roy Williams III, CHPA

Download PDF copy of the document

INTRODUCTION

A body worn camera (BWC) is a wearable audio, video, and/or photographic recording system. It is typically comprised of a camera, microphone and rechargeable battery, with data storage capabilities. Some products also offer live streaming and GPS location data. BWCs have a range of uses and designs, of which the best-known use is as a part of policing equipment. BWCs entered the law enforcement environment in approximately 2005 and have grown in use significantly over the past 10 years. In a 2013 study conducted by the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF), less than 25% of responding police departments reported using body cameras. By 2016, however, that number was as high as 95% for large cities and counties.1 In May of 2022, President Biden ordered all federal law enforcement officers to begin using BWCs.2 Presently, BWCs are used by a large number of law enforcement agencies with 25 states requiring officers to wear them.3 They are used by all law enforcement officers in the United Kingdom and at least 36 law enforcement agencies in Canada4,5 Proponents of BWCs believe that they are a deterrent to violence, can decrease the use of excessive force, improve transparency and trust and enhance incident documentation.

BWCs are used in the private sector in a variety of ways including action cameras for social and recreational use, within the world of commerce, in the military, journalism and in healthcare. Use in the private sector has also increased dramatically in the past few years, with estimates of more than $1 billion in growth in the industry between 2020 and 2025.6 In the healthcare sector, BWCs have been used in several ways including:

- Security officers and hospital-based law enforcement

- Emergency medical services

- Public health, specifically for home health visits

- Nurses in both psychiatric/behavioral health units and emergency departments

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that the rate of injuries from violent attacks against medical professionals grew by 63% from 2011 to 2018.7 The COVID-19 pandemic with staffing shortages, COVID restrictions, service delays, fatigue and burnout has further increased tension and frustration, leading to an even higher incidence of violence. A 2021 poll of more than 2,000 health care workers by the Canadian Union of Public Employees revealed that more than half had either experienced or witnessed an increase in violence since the beginning of the pandemic. Sixty-three percent of respondents reported they had experienced physical violence at their workplaces and 18% reported an increase in the number of incidents involving weapons since March of 2020.

The trend is similar in the U.S. In a 2022 survey by National Nurses United, the nation’s largest union of registered nurses, 48% of the more than 2,000 responding nurses reported an increase in workplace violence — more than double the percentage from a year earlier.

With the continued increases in healthcare violence, it is not surprising that tools like BWCs are being considered by more organizations. Unfortunately, there is not much aggregated information available about their use in the healthcare industry. There is minimal information available regarding how many facilities use them, how they are used, and whether empirical data is available to support their efficacy. There is also no regulation of BWCs in the private sector, though federal and state laws that were created for audio and stationary video recording such as CCTV systems apply. This article will examine the regulatory environment surrounding BWCs and how that environment affects healthcare, evaluate the advantages and potential limitations of their use, review two healthcare security case studies and discuss the best practices currently available for healthcare BWC programs.

REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT

There are varying laws throughout the United States that regulate BWCs for law enforcement. The laws primarily dictate when and how BWCs can be used, if the public can request the footage and how long video footage must be retained. However, while these laws provide useful best practices for managing a BWC program, they only apply in healthcare facilities that employ law enforcement officers. The laws that apply to private security officers are the same as those that apply to private citizens regarding recording in general. They are the same regulations that apply to stationary cameras in healthcare facilities and fall into three main categories: whether audio only recordings are permitted, how many parties must give consent or be aware of the recording and whether recording is restricted when an expectation of privacy exists.

Audio-Only Recording

The majority of states have legislation in place that it is illegal to record or “intercept” audio only recordings. These laws are focused on eavesdropping and were often created prior to the invent of security cameras that could also record audio.10 Conversely, there are no state regulations related to video only recordings without audio. All BWCs currently on the market do both audio and video recording, so they are in compliance with these laws.

What Consent Is Required

Consent laws consider whether or not it is legal to record someone on audio without their permission. Federally, it is legal to record a conversation with at least the consent of one person – typically the person who has initiated the recording. This is called the one-party consent law. The one-party consent law does not cover video recordings, but if there is a conversation involved, the rule applies. However, several states have implemented stricter regulations requiring the consent of all parties for audio recording. In these states, BWCs used by private citizens like security officers cannot record any audio without the express consent of those being recorded, but video recordings without audio would be permissible.

Restrictions Where Privacy Is Expected

This third category is where the laws become more complex. Many of the state laws were designed for the prevention of video voyeurism and were not conceived with BWCs in mind. In general, citizens in the US have an expectation of privacy in certain locations such as restrooms and changing rooms, and recording of any kind is often prohibited in these areas. These areas have typically been determined using the Katz test, which was established during the US Supreme Court case of Katz v. United States. This test defines the reasonable expectation of privacy in a two-pronged approach: first that a person exhibited an actual, subjective expectation of privacy and, second, that the expectation is one that society is prepared to recognize as reasonable.11 So, if the state has restrictions in place for recording in locations where a “reasonable expectation of privacy” exists, the use of BWCs in those areas would be limited.

However, as noted in the test definition, identifying these areas is subjective. Some states specifically spell out locations where recording is prohibited. For example, the Arizona law states:

“It is unlawful for any person to knowingly photograph, videotape, film, digitally record or by any other means secretly view, with or without a device, another person without that person’s consent under either of the following circumstances: in a restroom, bathroom, locker room, bedroom or other location where the person has a reasonable expectation of privacy and the person is urinating, defecating, dressing, undressing, nude or involved in sexual intercourse or sexual contact.”

A patient could be urinating, undressing or nude in a hospital room, potentially limiting the use of BWCs, at least when these activities are occurring under the Arizona law. There is certainly no expectation of privacy in public areas of hospitals, however, it is not nearly as clear cut when evaluating expectations of privacy within patient rooms. There have been multiple U.S. Supreme Court rulings about specific areas of hospitals and whether an expectation of privacy exists. These rulings have been focused on search and seizure of property and pertain to government agencies, but the expectation of privacy determinations would apply to the video/audio recording policies in states where “reasonable expectation of privacy” is part of the video/audio recording laws.

- Several cases have held that patients being seen in an Emergency Department have a diminished expectation of privacy due to the nature of how emergency departments are set up and how they typically operate

- Several cases have held that hospital rooms outside of the emergency department often have a diminished expectation of privacy. A 1994 case in Michigan concluded that while patients in hospital rooms may have some expectation of privacy in their closed closets, bags, and drawers, hospital rooms themselves are public areas where ‘‘doctors, nurses, and other hospital staff routinely go in and out of … at all hours of the day and night without regard to the patients’ wishes” and therefore the expectation of privacy is diminished. A 2022 case from Minnesota had similar findings

- Some cases have held that patient rooms do have a reasonable expectation of privacy in some circumstances. A 2002 New Jersey case involved a patient who had been involuntarily committed for psychiatric care and had been at the hospital for two weeks. The court held the patient had a legitimate expectation of privacy in the living area of his hospital room, focusing on the length of the patient’s hospital stay and that the room contained a bed, nightstand, and personal wardrobe, similar to a home living area

The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) disagrees with the supreme courts and feels there is an absolute expectation of privacy in Emergency Departments. They oppose the use of BWCs without the express consent of patients. In a June 2019 policy statement, they said:

“In emergency department (ED) patient-care areas, patients and staff have a reasonable expectation of privacy. Because audiovisual recordings made without explicit consent may compromise their privacy and confidentiality, such recordings should not be permitted, particularly when they contain personally identifiable information.”

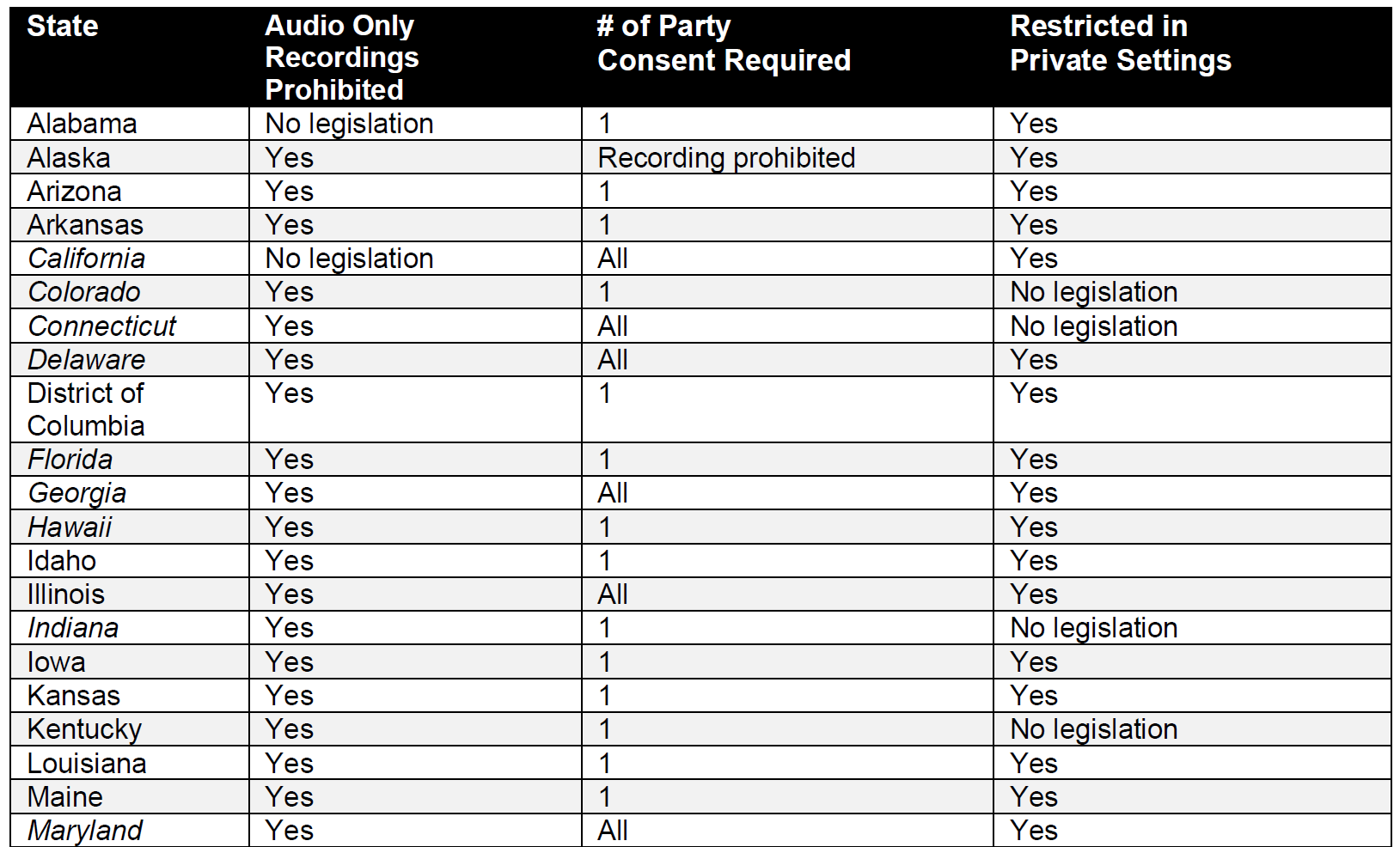

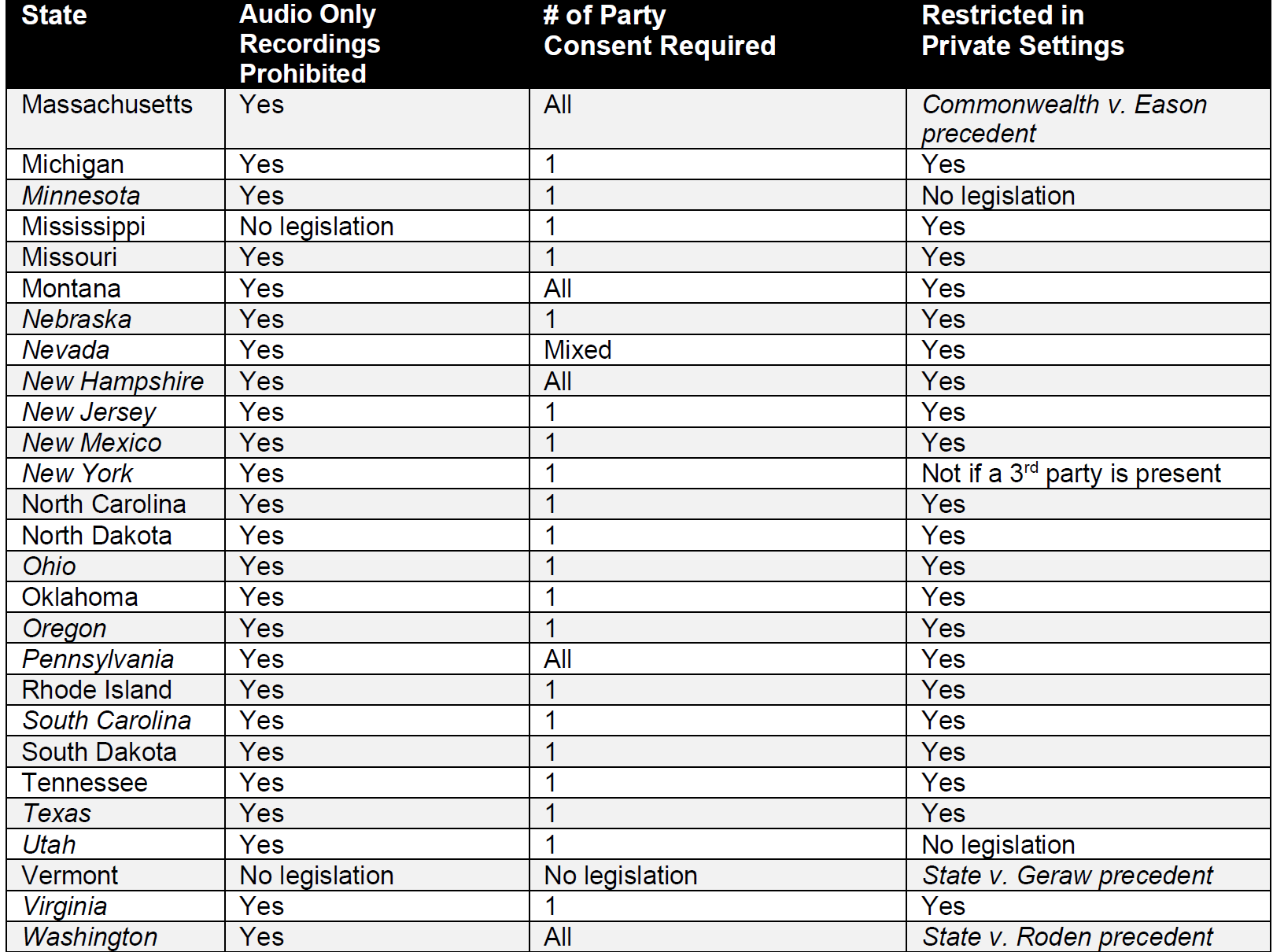

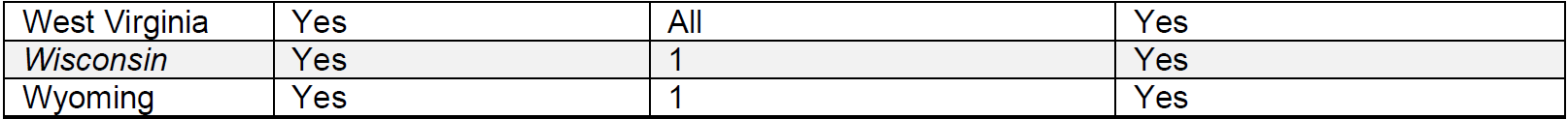

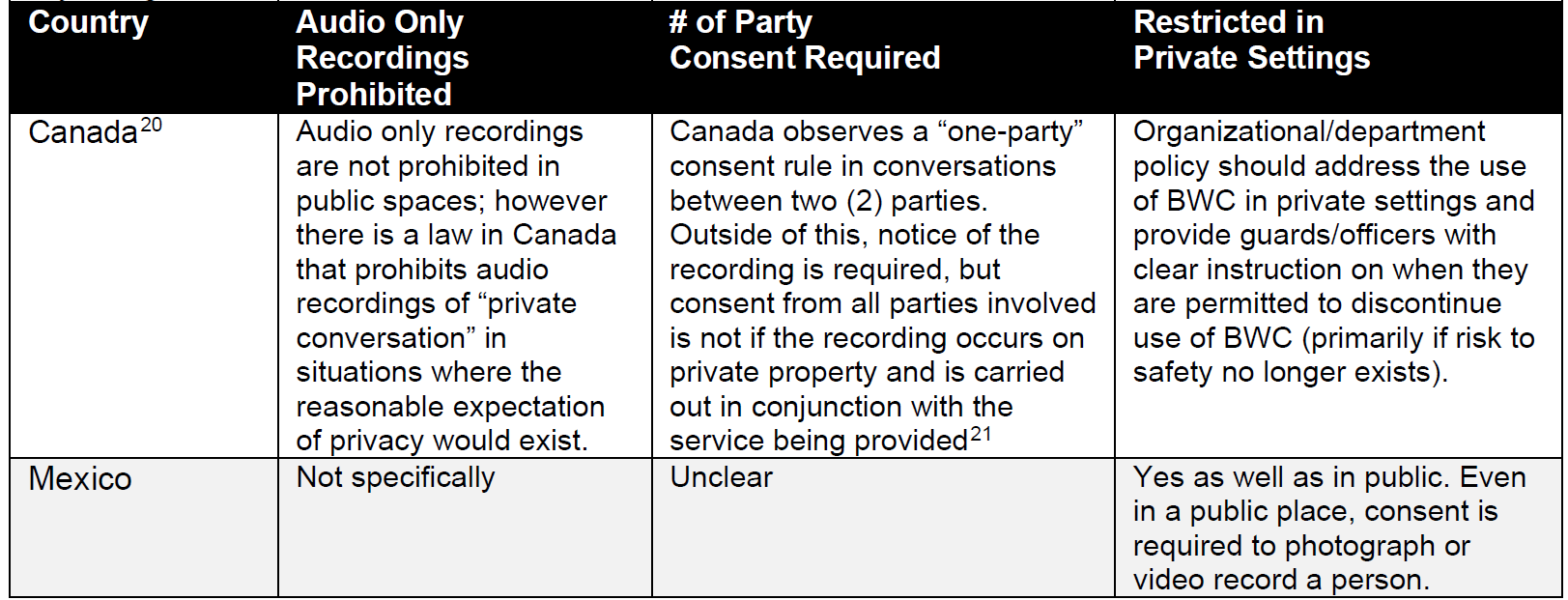

The table below was compiled using data from two sources and independent research by the author of this article for the U.S. states.18,19 The table details how all states and the District of Columbia view these three issues. For information purposes, the states that require law enforcement officers to use BWCs are in italics. Additional information for Canada and Mexico is cited individually. Specific statutes vary. This table is intended to be a basis for additional research and may not be comprehensive.

HIPAA and Other Privacy Laws

When considering privacy issues related to BWCs, it is also important to consider healthcare privacy regulations such as:

- The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in the U.S.

- The Personal Health Information Protection Act 2004 (PHIPA) and the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA) in Canada

- The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union. Note: the GDPR is not a healthcare specific privacy law, but applies to all personal identifiable data which includes the healthcare sector

These regulations provide strict guidelines for protected healthcare information (PHI). Generally speaking, these regulations address the disclosure and storage of PHI, not how it is obtained or gathered,23 so none expressly prohibit using cameras during patient care or in patient care settings. Under HIPAA specifically, video, photo and audio recordings are permissible for the purposes of treatment, payment and healthcare operations.24 Security purposes would fall under healthcare operations as permissible activities. Under PHIPA, video recording is permissible as long as the “highest security precautions” are taken to protect any PHI captured on video. The GDPR has similar language, listing video surveillance in general as a “high risk operation requiring particular attention.

It is clear that healthcare privacy laws must play a large role in developing a strong BWC policy. Concerns about violating privacy regulations often cause apprehension among hospital administrators, risk managers, privacy and compliance personnel, human resources managers, and lawyers. This can be one of the biggest challenges to implementing a BWC program.27 Later in the article when discussing best practices, we will cover how to protect PHI that is captured in BWC footage.

Industry Standards

Given the absence of specific laws regulating the use of BWCs by security officers, one must look to professional industry organizations for standards and guidance. Unfortunately, there are minimal standards available. ASIS International, one of the largest worldwide professional security networking organizations, does not offer a standard or best practices for BWCs.28 Neither does the National Association of Security Companies (NASCO), the nation’s largest contract security association.29 After searching through multiple trade organizations and reaching out to several, only the International Association of Healthcare Security and Safety (IAHSS) and the Data Protection Commission of Ireland have published standards or guidance related to the private security use of BWCs.

IAHSS

- The decision-making process for introducing BWCs should include a multi-disciplinary team

- Develop policy and procedures as to when the BWC is authorized and how it is deployed. Policy should include:

- Establishing appropriate use and deployment

- Determining when not to deploy

- Establishing expectations for initial and ongoing training and documentation

- Defining the process to inform individuals they are being recorded when required

- Reporting requirements that define when security staff do not activate the BWC during expected events or fail to record the duration of the event

- Determining the retention requirements of captured recordings and the factors for when to include in the medical record and other required reports

- Downloading, redacting, labeling, storing, and deleting captured audio and video recordings

- Determining who is authorized to view, share, release, and delete audio and video recordings, and to whom

- GUIDANCE FOR POLICIES AND INTERVENTIONS IN NON-U.S. HOSPITALS

- BWC recordings should be treated the same as other protected health information and reside on a network that meets patient privacy program requirements

Data Protection Commission of Ireland

- Utilization of cameras must be lawful and fair

- Officers have an obligation to be transparent about recording

- Must minimize the amount of personal data recorded

- Must determine a retention policy appropriate for the organization and abide by said policy

- Have a process in place for responding to private requests for the camera recordings

BENEFITS AND LIMITATIONS

Benefits

There are several potential benefits to using a BWCs in the healthcare setting. They are small, lightweight and can withstand environmental extremes such as high temperatures and water. They are durable and will likely withstand a physical interaction or altercation. Because they are compact and typically have built in storage, they can be used for long periods of time without causing discomfort to the wearer or requiring recharge. AXON, one of the major worldwide suppliers of BWCs, touts them as a wonderful tool to decrease threatening behavior, hold people accountable, de-escalate incidents and preserve the truth.

The majority of studies on BWCs have been conducted in the law enforcement field, but they have applicability to other industries. For example, a 2017 randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving 400 officers in the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department found that officers who wore BWCs generated significantly fewer complaints and use of force reports relative to control officers without cameras.33 Another study published in 2017 conducted an RCT involving 430 police shifts in a large British police force over a six-month period. The study found a 50% reduction in the odds of force used when BWCs were present compared with control conditions.34 A 2012 study conducted in Rialto, California randomly assigned BWCs to various frontline officers across 988 shifts over the course of one year. The study found that there was a 60% reduction in officer use of force incidents following camera deployment as well as an 88% reduction in the number of citizen complaints.

A few smaller studies have been conducted in the healthcare setting, but they were not security specific. In 2014, the use of body-worn cameras by nurses was tested in the United Kingdom on two wards at a high-security psychiatric hospital. The study noted a small reduction in incidents of assaults on staff. Moreover, there was a “notable reduction in antisocial and aggressive behavior”, according to a spokeswoman for the West London NHS trust, which runs the facility where the study occurred. In 2019, Ellis et. al. conducted a pilot study evaluating BWC use in mental health wards. 50 cameras were used among nursing and security staff in seven mental health wards over a period of four months. They found that the use of BWCs was associated with a reduction in the overall seriousness of aggression and violence in reported incidents and with a marked decline in the use of tranquilizing injections during restraint incidents.

An additional benefit of BWCs is the opportunity to use the footage for training, quality control and assisting with response strategies.38,39 While some of this information can be gleaned from standard CCTV footage, BWCs provide a different perspective and provide audio, which many CCTV systems do not. This may present a more complete picture of situations and make training scenarios more realistic. Additionally, BWCs are mobile, enabling recording to occur not only in hospital common areas, but in all areas of the facility where they can capture the exact nature of aggressive interactions.40 They are a significant force multiplier of a traditional CCTV system, essentially eliminating blind spots.

Disadvantages and Limitations

There are several studies about the effect of BWCs on violence, assaults and use of force that had significantly different findings than those mentioned above. Ariel et. al. conducted a meta-analysis of multi-site, multi-national RCTs from 10 discrete tests. The analysis, which included 2.2 million police officer-hours, looked at police use of force but also assault against officers which was not a component of the original studies. Averaged over the 10 trials that were reviewed, BWCs had no effect on police use of force and led to an increased rate of assaults against officers wearing cameras.41 Another study to consider is a 2017 RCT of more than 2,200 officers in the Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police Department. For each of the metrics tracked (use-of-force incidents and civilian complaints, among other outcomes) the study did not find any statistically significant differences indicating a change in either police or civilian behavior after adopting BWCs.42 Finally, in 2020, Lum et. al. conducted a literature review of 38 RCTs or quasi‐experimental research designs that measured police or citizen behaviors relevant to BWCs. Almost all studies were carried out in a single municipal jurisdiction in the United States. Among other conclusions, their review found that the use of BWCs did not have consistent or significant effects on officers’ use of force or citizens resisting arrest.

Conflicting data on efficacy is not the only limitation of BWCs to consider. There are HIPAA and privacy considerations as previously discussed. There is also a concern about trust. Even if healthcare providers are not the ones specifically wearing body cameras, their presence in the environment could alter provider-patient interactions. Megan Allyse, an ethicist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota said there may “be a cooling effect on patients’ and healthcare providers’ being honest with each other. And this is a million times more when you have stigmatized conditions like mental health or drug use and addiction.”

There are also some limitations in the camera itself, as noted by Dr. Bill Lewinski, executive director of the Force Science Institute in a special report. Some of the issues noted include:

- A camera does not follow the eyes of the wearer. “A body camera photographs a broad scene, but it can’t document where within that scene you are looking at any given instant,” Lewinski said. “If you glance away from where the camera is concentrating, you may not see action within the camera frame that appears to be occurring ‘right before your eyes’.”

- A camera may see better than human eyes in low light conditions. “The high-tech imaging of body cameras allows them to record with clarity in many low-light settings,” Lewinski said. “When footage is screened later, it may actually be possible to see elements of the scene in sharper detail than you could at the time the camera was activated.”

- A camera records in 2D without the benefit of depth. “Depending on the lens involved, cameras may compress distances between objects or make them appear closer than they really are,” Lewinski said. “Without a proper sense of distance, a reviewer may misinterpret the level of threat an officer was facing.”

Lastly, cost must be considered a limitation to the implementation of BWCs. Not only is there a cost for the cameras themselves, but there are also charging stations and carriers as well as software and data storage equipment necessary to support appropriate video retention to consider. Data storage is often set up in a cloud-based environment to limit the cost of purchasing and maintaining large storage servers; however, cloud-based storage is an annual cost, not a one-time fee. A 2021 cost study for the state of Maryland estimated that the annual cost for a camera program, including the cost of support personnel and storage was about $2,445 per officer/camera. The lower and higher ends of the range of costs were $1,791 and $3,788 per officer/camera, respectively. If a facility chooses to implement the cameras in a local environment with onsite storage, the annual cost would be lower but there would be a larger upfront cost for data storage and servers. Depending on the number of officers equipped with BWCs and the amount of days encompassed by the video retention program of the organization, storage costs can be enormous, in the tens of thousands for smaller entities to the hundreds of thousands for larger. That is a hefty cost to consider when weighing the pros and cons of a program, though factors like decreased force incidents and decreased legal costs following incidents would potentially offset the costs.

CASE STUDIES

As mentioned earlier in this article, there are no studies or estimates that quantify the number of healthcare facilities that have implemented BWCs programs. The information is gleaned case by case by scouring the internet for case studies, policies or position statements from facilities on BWCs. Below are two examples of healthcare entities that have implemented BWCs with some insight into their experiences. To provide these case studies, the author of this article interviewed the program director for each organization, asking the same list of questions to each.

CoxHealth

Location: Springfield, Missouri

# of Hospitals: 6 and 80+ clinics

# of Licensed Beds: 1,194

# of Officers in the Program: 80 FTE

Length of Time in Use: 4 years

Reasons for Implementing: The intention of the program was twofold. Goal number one was protecting the organization and the officers when they interacted with the public. We use the cameras for all interactions – from a slip and fall to a physical altercation. Many of these incidents have historically been one on one, which too often creates a “he said/she said” situation. The BWC creates an unbiased third party in those situations. Goal number two was to use the camera as a deterrent to some behaviors. Missouri is a one-party consent state, so we do not have to announce that an event is being recorded. Sometimes we choose to, which has de-escalated some situations. It does not work every time, but it can sometimes lessen the aggression that we encounter.

Set Up: We use an AXIS BWC that integrates into our Genetech video management system. They also integrate with the 1,400 fixed cameras throughout our facilities. The cameras are slightly larger than a credit card and about ½” thick. Video sits on the video management system (VMS) behind the hospital’s fire wall and is the property of CoxHealth; nothing is cloud based. The video record is considered part of the patient’s overall interaction with the health system.

Policy: Our policy went through multiple iterations, but that is true any time you are bringing on something new. When you are out a little in front of the industry, you go through multiple iterations. We reached out to learn what others were doing. Legal, risk, nursing and the executive team were all involved in the policy development. The BWC rollout should not surprise anyone and we worked hard to get buy-in from all key stakeholders on the front end. If we have a serious incident that occurs on this campus, we have a multi-disciplinary review committee that evaluates the incident and BWC footage is a big part of the review.

Challenge: There will always be questions about HIPAA. We have a very engaged and informed legal department. They were an integral part of the decision to move forward with BWCs as well as with the development of the policy.

Advice to Those Considering a Program: Technology has come a long way in the last few years. There are multiple options available to consumers. Anyone considering a program needs to do their homework. Some cameras have unique features. For us, the marriage to our VMS was critical. We also wanted a system that was simple in its application. The camera controller assigns the camera at the beginning of the shift. When the officer puts the camera into the controller at the end of the shift, it automatically downloads. The tool must be useable by the officer. Additionally, our cameras buffer which means they will record 30 seconds prior to when the button was pushed. This is helpful in situations that develop rapidly.

Bottom Line: Statistically, we did not see a decrease in violent incidents. We do see some situations de-escalating more quickly with the use of the cameras. But we can clearly show that it has caused a reduction in frivolous lawsuits.

Sinai Health

Location: Toronto, Ontario

# of Hospitals: 2

# of Licensed Beds: 831

# of Officers in the Program: 170

Length of Time in Use: 15 years

Reasons for Implementing: BWCs were initially implemented during a pilot initiative at Sinai Health in 2008, as part of a clinical research endeavor aimed at investigating their potential to mitigate workplace violence incidents within the Emergency Department. Officers participating in this study were equipped with BWCs and provided specific communication scripts to inform individuals/patients in escalating situations that they were being recorded during their interactions in order to assess whether the announcement of surveillance through BWCs would serve to limit behavior and aid in de-escalation.

At the end of the trial period, it was determined that the introduction of BWCs had no discernible impact on behavioral outcomes or the de-escalation of incidents. Despite this outcome, Sinai Health opted to retain and further explore the use of BWCs, as they had already been procured for the study, which allowed us to continue exploring alternative benefits and applications within the hospital setting.

After almost a decade of use and exploring various potential benefits after the initial study, our attention shifted towards harnessing the capabilities of this technology for the enhancement of clinical/organizational quality improvement practices by presenting the unbiased, objective account that BWCs offer. The BWCs continue to show no effect in de-escalating violent behavior in our setting, but by offering security’s documentation and BWC recordings as supplemental material for incident, case and process review within the hospital, we have found them invaluable for quality improvement, training and staff perception of safety.

Set Up: We maintain a locally hosted BWC software and video storage behind an internal fire wall to limit risk of hacking and unauthorized access to footage. Only a small number of department personnel have access to the system and the software logs all activity pertaining to the footage including what is accessed and by whom as well as if a video is altered or exported. Videos are automatically deleted after 30 days unless they have been flagged for retention by leadership and/or key stakeholders. Access and review of the footage is governed by department policy.

Policy: There is an organizational policy that governs all video programs. The policy can be viewed as intentionally generic to allow flexibility in its application and reliance on subsequent department procedure. The specific document related to the use of BWCs is a departmental procedure that can be modified and updated more easily to meet the needs of the hospital and educational needs of the officers. As we strive to maintain the culture of BWCs as an additive service to the staff, patients and people we support, officers announce that they are recording for “safety and documentation purposes.” Very rarely is BWC footage accessed as a means to discipline without notification of incident, but instead to supplement the culture of continuous learning and improvement within the department. We are constantly reviewing and updating the policies to help promote this aspect of the department to drive a culture of service refinement and growth.

Advice to Those Considering a Program: Considering a program is one thing, but ensuring you have support for the program is something else. You must evaluate the culture at the organization and determine how the use of BWCs is going to further that culture and the organizational goals. It must speak to every single person in the organization. Have at least one use-case that each group/stakeholder would otherwise benefit from and establish clear limitations to the systems use to emphasize accountability in protecting each group/stakeholder from misuse. It is essential to secure executive-level sponsorship for BWC initiatives. These devices represent a substantial investment, so when implementing a BWC system, emphasis on training and education becomes paramount. It is crucial that our officers convey the right messages and have a comprehensive understanding of the technology that the organization has ultimately agreed to support.

To ensure a successful rollout, widespread awareness within the organization is a must. Equally important is the establishment of robust processes, along with the ability to effectively communicate these processes. Topics such as cybersecurity, video retention policies and controlled access to recorded footage are absolutely critical aspects that require attention and repeated communication to ensure the overall success of a BWC program.

Bottom Line: The BWC program has shown its biggest advantages to the Sinai Health security program by educating senior executives and clinical partners on the situations faced by front-line staff, clinicians and security officers by allowing them to appreciate the successes and difficulties faced through the objective documentation BWCs permit. One of our roles as security professionals is to educate and BWCs have been a wonderful tool for that. BWCs dispel many of the unknown elements that an organization faces when reviewing events and can lead to more support in building the framework for new programs, staffing, etc. We have been fortunate to receive such support from the organization over the last few years because we have been able to successfully integrate ourselves into organizational/clinical review processes by using this technology to advocate in support of what nurses, clinicians and officers deal with daily. We like to tell the officer “you have to be a master of your tools,” because, at the end of the day, BWCs are just another tool in an officer’s arsenal to help promote service. Ultimately, it comes down to having defined processes and standards that reflect your organization and support everyone equally.

If you can carry out the process to a high standard, that’s when you’ll find success.

IMPLEMENTATION BEST PRACTICES

There are many advantages and limitations to weigh when considering implementing a BWC program in the healthcare environment. Given the limited amount of direct guidance on the subject from law makers and industry organizations, it is essential that healthcare organizations work to follow all best practice information available when implementing a program.

Strengths and Limitations

The present review highlights many valuable tools and resources that can be implemented. Understanding the patient risks of the homeless population can provide valuable insight into issues that may arise. There were a variety of interventions that target many aspects of patient care that are more common among patients who are homeless. Many of these practices can be cost-effective measures to help improve patient health and well-being. Incorporating interventions, especially multilevel interventions, may have a dramatic impact on homeless patients.

There are some limitations to the present study and the information available on the topic. First, there was an overall lack of literature available on violence in emergency room and hospital settings for homeless patients. Additionally, not all studies used the same metrics for success which can limit overall comparison. While there were a variety of studies from around the world, specific conditions within each country may limit generalizability to other parts of the world. Also, few national policies existed to outline homeless patient discharge procedures and were not always adhered to by individual hospitals (Gallaher et al., 2020).

Policy Development

While the contents of the BWC policy are important, what may be more crucial is the composition of the team engaged to create the policy. Depending on the culture of an organization, there may be various levels of resistance to adopting a new technology. Including the right team members from the inception of the project will give the best chance of comprehensive adoption and commitment to the program. At minimum, the team should include:

- Senior leadership

- Clinical leadership

- Security leadership as well as security officers who will be using the technology

- Risk management and legal

- Compliance, accreditation and privacy

- Information technology and cybersecurity

- Public information office

- Human resources

What to Record

Establishing what to record is a major policy point to resolve early in program development with the multi-disciplinary team. Continuous 24/7 recording is not practical, nor is it an efficient use of video storage space, so the development team must decide in what circumstances the camera should be activated. Some common choices include:

- Every interaction with a security officer. In this circumstance, every time an officer interacts with anyone for any reason, the camera would be activated. This ensures broad coverage of an officer’s interactions and will likely catch a few incidents that more restricted programs may not. There may be a further clarification as to whether this includes interaction with employees or only patients and guests. If using this approach, it must be considered if there should be exceptions for sensitive situations such as interviewing a crime victim or talking to a distraught family member

- Every security incident. What constitutes a security incident should already be a defined component of security policy. If it is not, it would typically include when a security officer is called for a security purpose. Officers often have responsibilities that would not be considered security incidents such as helping a guest find their car, assisting persons with physical limitations out of vehicles or collecting lost and found items. In this model, those types of interactions would not be recorded, but a security call to take a theft report or escort money would be

- Only incidents of anger or aggression. With this option, only incidents that involve verbal or physical aggression would be recorded. If this is the chosen path, it is critical to select a BWC that has a buffering capability. As aggressive incidents often develop quickly, the buffering feature records a set amount of time before the button was pushed to activate the camera

- Location based. With this model, officers would activate the camera always in areas that have been identified by the organization as “high risk.” This may include the emergency department, inpatient psychiatric unit, intensive care unit, neonatal intensive care unit, labor and delivery and/or pediatric units. This type of arrangement would provide increased privacy protection to patients in areas where the risk is low for violence, however, it would likely miss some aggressive incidents. Another location-based option would be to say that recording occurs in all locations, except for certain locations where the organization has deemed there is an increased expectation of privacy. This could include inpatient rooms or a behavioral health unit for example

The determination of which option is best depends on the culture of the organization and the goals of the BWC program. If the program goal is to capture all aggressive incidents, it may be beneficial to begin with the most restrictive model and then expand if all aggressive incidents are not being captured. If the goal of the program is quality improvement for clinical care or security interactions, a broader definition may be the better route.

Notification of Recording

State or country laws may dictate that it is necessary to post signage or announce when a BWC is in use. However, even in states where it is not required, it may be beneficial to do so. Sometimes the presence of a BWC coupled with a warning or signage that cameras are in use is enough to deescalate a threatening situation. That benefit will not be realized without posted signage and scripting from officers about the activation of a BWC.

Protecting PHI

To be in compliance with all the aforementioned privacy laws, the policy must define steps that are taken to protect PHI, particularly how that data is protected and how access is limited only to those who have a business need to review the footage.

How the data will be stored to limit access by parties with malintent should be determined in conjunction with the information technology and cybersecurity teams. First, the software system should use end to end encryption whenever data is being transmitted or stored. This prevents access by individuals who do not have a decryption key.54 This discussion should also include if data storage will be cloud-based or on premises. If the footage is being stored by a cloud-based software solution, a Business Associate Agreement (BAA) should be in place.55 If it is on premises, it should be behind a firewall and ideally on a security network that is separate from the primary hospital network.

To prevent unauthorized users from viewing video surveillance, it is essential that the surveillance software is password protected. Each employee that requires access should be granted unique login credentials to access video surveillance, and there must be a credentialing hierarchy that limits access to recorded video. Once an officer has uploaded files and appropriately associated them with reports, that officer should no longer have routine access to the footage. Additionally, the software must have auditing controls to ensure that unauthorized users are not accessing video surveillance, or authorized users are not abusing their privileges. “By keeping an audit log, administrators can establish regular data access patterns for each employee, allowing them to easily identify when data is being accessed outside the norm. When data access is outside the norm, this usually means that either the employee is abusing their privileges and therefore violating HIPAA, or an unauthorized user, such as a hacker, has gained access to the employee’s login credentials.”

Who outside of the security team has access to BWC footage should be established. Is it restricted only to a Quality Improvement (QI) team? Do IT support personnel need access? Are departmental directors able to view footage of incidents that occur in their areas of responsibility? If an employee is captured in a video, does the employee have a right to view it? All of these questions should be addressed in the policy.

Quality Improvement Program

The benefits of using BWC footage for QI have been well demonstrated across a variety of studies; however, how best to use the cameras for QI depends again on the goals of the program. They can be used strictly to evaluate security interactions, but can also be used to evaluate de-escalation skills, clinical practices and communication. But there must also be a QI program in place evaluating specifically the BWC program. At minimum, it should include a review process for if a camera fails, if a camera is not properly activated during an incident or if the a camera provides insight that the handling of an incident had opportunities for improvement

Training

Training on the device is pretty simple; the cameras and software are user friendly technology. The training areas of focus should be on the policy itself and addressing concerns. The nuances of when to record, when not to record, what scripting to use, etc. may take a while for officers to grasp. Additionally, there will probably be concerns amongst the officers as well as general staff throughout the facility about the introduction of BWCs. It is imperative to train all team members on the purposes of the program and how the footage will be used. The program will not have a successful roll out if people are surprised by the introduction of BWCs or their concerns have not been addressed.

Retention Program

The majority of policies reviewed default to 30, 60 or 90 days of retention for video that has not been flagged as part of evidence. Flagged items are either stored indefinitely until no longer needed or have a new retention period based on the statue of limitations for an action to be filed. The organization must decide what is appropriate with input from the risk and legal teams who will have insight into the typical length of time between incidents and the filing of legal action in the area. Overall retention is a critical concern when thinking about cost. The longer the retention period, the more videos will need to be stored at any given time.

Release of Footage

The last critical item for consideration in the policy is under what circumstances BWC footage will be released outside of the healthcare organization. If the BWC footage for 19

an incident is considered part of the patient’s record, he/she may have a legal right to request the footage. In some states, this is true, even if the footage is not considered part of the patient’s record. Law enforcement agencies may also be interested in requesting footage if it shows evidence of a crime, such as an assault. During the policy development phase is the right time to make these determinations. Healthcare organizations should meet with local law enforcement to discuss how the footage can be used and under what circumstances, if any, the healthcare organization is willing or able to release it. It should also be discussed whether the ability to redact footage is part of the implementation plan. Redacting footage can be costly, depending on the software solution selected, but it is necessary to protect the privacy of bystanders, family members, patients and employees who may be captured in the footage but not be part of the incident. There could also be data visible on computer screens or medical information on monitors that should be redacted prior to release. If there are any circumstance under which the healthcare organization would consider releasing BWC footage to the general public or news media, the public information office should be involved in the discussion as well.

CONCLUSION

Implementing a BWC program can offer many benefits to a healthcare organization. It may reduce incidents of violence, increases the perception of safety and has shown excellent results for quality improvement and training. There are several potential disadvantages including contested efficacy, privacy concerns, technical limitations and cost. The case studies highlighted that BWCs are a tool that can be very useful in the healthcare industry if properly implemented. Successful implementation of a BWC program requires:

- Senior leadership support

- A clear definition of the program goals and how BWCs will supplement the organization’s culture and other safety programs

- A well thought out policy that is developed by a multi-disciplinary team

- Thorough vetting by the legal department to ensure the program complies with the laws and regulations of the jurisdiction

- Technical product selection that considers the program goals as well as IT infrastructure and security needs

- A rollout process that includes organization wide training

The use of BWCs is continuing to grow in healthcare, but the research is limited. The healthcare industry would benefit from research to determine how many organizations are using BWCs, how they are being used and what efficacy they are showing specifically in the healthcare sector.

AUTHOR

Sarah J. Spears has been in the safety and security field for more than 20 years. She holds an M.S. in Safety and Emergency Management from the University of Tennessee and a B.A. in Journalism from the Ohio State University. She is a Certified Healthcare Security Officer and Nationally Registered Paramedic. She has worked in multiple industries including amusement parks, healthcare, manufacturing and special events. Previously, she served in the Arlington Texas Fire Department as a special event emergency planner participating in public safety planning for large events including the 2010 and 2011 World Series and Super Bowl 45. Ms. Spears may be reached at sarahhenkel@sbcglobal.net.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alalouff, Ron. “The rise of body-worn cameras in security, retail and healthcare.” IFSEC Insider (2021). Last accessed on July 19, 2023 at https://www.ifsecglobal.com/video-surveillance/rise-of-body-worn-cameras-security-retail-healthcare/

Amdt 4.3.3 Katz and Reasonable Expectation of Privacy, (Constitution Annotated). Last accessed July 21, 2023 at https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/essay/amdt4-3-3/ALDE_00013717/

American College of Emergency Physicians, Policy Statement (June, 2019). Last accessed July 21, 2023 at https://www.annemergmed.com/article/S0196-0644(17)30506-1/fulltext

Ariel, Barak et al. “Wearing body cameras increases assaults against officers and does not reduce police use of force: Results from a global multi-site experiment.” European Journal of Criminology, Vol. 13, Iss. 6 (2016): 744–755.

Ariz Rev. Stat. § 13-3019 (A)(1). Last accessed July 15, 2023 at https://codes.findlaw.com/az/title-13-criminal-code/az-rev-st-sect-13-3019/

ASIS. https://www.asisonline.org/publications–resources/standards–guidelines/

AXON. https://www.axon.com/news/security-bwc-advantages

Bakst, Brian and Ryan J. Foley. “For police body cameras, big costs loom in storage.” Police 1 by Lexipol (2015). Last accessed August 28, 2023 at https://www.police1.com/police-products/body-cameras/articles/for-police-body-cameras-big-costs-loom-in-storage-4IR8ZdjJCHIRHHv9/

Bartolac, John. “Body-worn video camera use extends beyond policing.” Security Magazine (2021). Last accessed July 25, 2023 at https://www.securitymagazine.com/articles/96673-body-worn-video-camera-use-extends-beyond-policing

Batterton, Brian. “Eighth Circuit Holds No Reasonable Expectation of Privacy in Hospital Room.” Legal Liability and Risk Management Institute (2023). Last accessed July 19, 2023 at https://www.llrmi.com/articles/legal_updates/2023_us_v_mattox/

Bernette, Angela. “Searches of Hospital Patients, Their Rooms and Belongings.” Healthcare Law Monthly, Iss. 10 (2012): 2-9.

Black, Ryan. “Should Healthcare Employees Wear Body Cameras?” Chief Healthcare Executive (2017). Last accessed July 25, 2023 at https://www.chiefhealthcareexecutive.com/view/should-healthcare-employees-wear-body-cameras

Boyle, Patrick. “Threats against health care workers are rising. Here’s how hospitals are protecting their staffs.” Association of American Medical Colleges (2022). Last accessed August 30, 2023 at https://www.aamc.org/news/threats-against-health-care-workers-are-rising-heres-how-hospitals-are-protecting-their-staffs

Braga, Anthony et. al. “The Benefits of Body-Worn Cameras: New Findings from a Randomized Controlled Trial at the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department.” US Department of Justice (2017): 1-79. Last accessed July 25, 2023 at https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/251416.pdf

Broccolo, Bernadette and Daniel Gottlieb. “Does GDPR Regulate Clinical Care Delivery by US Health Care Providers?” McDermott, Will & Emery (2018). Last accessed August 28, 2023 at https://www.mwe.com/insights/does-gdpr-regulate-us-clinical-care-delivery/

Butler, Alan. Administrative Director of Public Safety and Security at CoxHealth (alan.butler@coxhealth.com). Interview conducted by author, August 2023.

Cardoso, Tom and Robyn Doolittle. “Police body cameras are touted as an accountability tool. But getting the footage is a challenge.” The Globe and Mail (2023). Last accessed July 19, 2023 at https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-police-body-cameras-are-touted-as-an-accountability-tool-but-getting/

Compliancy Group. https://compliancy-group.com/hipaa-and-use-of-surveillance-video/

“CoxHealth Deploys Axis Body Worn Camera Solution” Security Info Watch (2022). Last accessed on August 27, 2023 at https://www.securityinfowatch.com/video-surveillance/cameras/mobile-vehicle-body-worn-surveillance/press-release/21260594/axis-communications-coxhealth-deploys-axis-body-worn-camera-solution

Crowe, Matthew and Gene Lauer. “Cost Analysis of Police Body-Worn Cameras in Maryland: A Review and Results of National Studies Applied to Maryland.” Energetics Technology Center (2021). Last accessed July 26, 2023 at https://www.etcmd.com/media/article/2021-08/cost-analysis-police-body-worn-cameras-maryland-review-and-results-national

Ellis, Tom et. al. “The Use of Body Worn Video Cameras on Mental Health Wards: Results and Implications from a Pilot Study.” Mental Health and Family Medicine, Vol. 15 (2019): 859-868.

Force Science Institute. “10 limitations of body cams you need to know for your protection.” Police 1 by Lexipol (2014). Last accessed August 29, 2023 at https://www.police1.com/police-products/body-cameras/articles/10-limitations-of-body-cams-you-need-to-know-for-your-protection-Y0Lhpm3vlPTsJ9OZ/

“Guidance on the use of Body Worn Cameras or Action Cameras.” Data Protection Commission (2020). Last accessed August 27, 2023 at https://www.dataprotection.ie/sites/default/files/uploads/2020-04/Guidance%20on%20Body%20Worn%20Cameras%20or%20Action%20Cameras_Jan20.pdf

Hattersley, Robin. “Using Body-Worn Cameras in Healthcare Security: Piedmont Healthcare’s public safety officers now use body-worn cameras. Here’s why and how their organization adopted this technology and the results.” Campus Safety (2021). Article and podcast last accessed August 27, 2023 at https://www.campussafetymagazine.com/podcast/using-body-worn-cameras-in-healthcare-security/

Henstock, Darren and Barak Ariel. “Testing the effects of police body-worn cameras on use of force during arrests: A randomised controlled trial in a large British police force.” European Journal of Criminology, Vol. 14, Iss. 6 (2017): 720-750. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370816686120

IAHSS Healthcare Industry Guidelines, 13th Edition. “02 Security Department Operations: 10 Body Worn Cameras in the Healthcare Security Program.” (2022). Available online to IAHSS members or for purchase.

Katz, Eric. “Biden Orders All Federal Law Enforcement to Wear Body Cameras.” Government Executive (2022). Last accessed July 19, 2023 at https://www.govexec.com/management/2022/05/biden-orders-all-federal-law-enforcement-wear-body-cameras/367381/

LaPedis, Ron. “Maximizing the benefits of police body-worn cameras: Tips and tricks for law enforcement.” Police 1 by Lexipol (2023). Last accessed July 25, 2023 at https://www.police1.com/police-products/body-cameras/articles/maximizing-the-benefits-of-police-body-worn-cameras-tips-and-tricks-for-law-enforcement-YWK76pQd99EeUOVg

Lum, Cynthia et al. “Body‐worn cameras’ effects on police officers and citizen behavior: A systematic review.” Campbell Systematic Reviews, Vol. 16, Iss. 3 (2020): 1-40. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1112

Marcisz, William. “A Legal Lens on Body Cameras Worn by Hospital Security Officers.” Strategic Security Management Consulting (2022). Last accessed on August 27, 2023 at https://ssmcsecurity.com/healthcare-security-consultant/a-legal-lens-on-body-cameras-wornby-hospital-security-officers/

Miller, Lindsay, Jessica Toliver, and Police Executive Research Forum. “Implementing a Body-Worn Camera Program: Recommendations and Lessons Learned.” Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services (2014). Last accessed September 23, 2023 at https://www.justice.gov/iso/opa/resources/472014912134715246869.pdf

Mulholland, Hélène. Can body cameras protect NHS staff and patients from violence? (The Guardian, 2019). Last accessed July 21, 2023 at https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/may/01/body-cameras-protect-hospital-staff-patients-violence-mental-health-wards

National Association of Security Companies. https://www.nasco.org/

Nicholson, Paul. Senior Manager, Security & Emergency Preparedness for Sinai Health (pnicholson@baycrest.org). Interview conducted by author, August 2023.

Page, Wolfberg and Wirth. “EMS Body-worn Camera Quickstart Guide: Legal Considerations for EMS Agencies.” National Emergency Medical Services Information System (2021) v. 1. Last accessed September 23, 2023 at https://nemsis.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/EMS-Body-worn-Camera-Quickstart-Guide_Legal-Considerations_06.2021.pdf

Patient Ombudsman Annual Report (2021-22). Last accessed August 29, 2023 at https://patientombudsman.ca/portals/0/documents/patient-ombudsman-annual-report-2021-22-en.pdf

Police Worn Body Cameras Legislation Tracker. https://apps.urban.org/features/body-camera-update/

Recording Law. https://recordinglaw.com/canada-recording-laws/

Steele, Douglas. “Body Cameras and Emergency Medical Service Providers: What are the Privacy Considerations?” Journal of EMS (2017). Last accessed July 21, 2023 at https://www.jems.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Body-Worn-Cameras-Paper.pdf

“The GDPR and Video Surveillance.” GDPR Informer (2017). Last accessed August 28, 2023 at https://gdprinformer.com/gdpr-articles/gdpr-allows-video-surveillance

U.S. Bureau of Justice Assistance Body-Worn Camera Toolkit. https://bja.ojp.gov/program/bwc/topics#gcov4e

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/index.html

World Population Review. https://worldpopulationreview.com/state-rankings/body-camera-laws-by-state

Yokum, David, Anita Ravishankar and Alexander Coppock. “Evaluating the Effects of Police Body-Worn Cameras: A Randomized Control Trial.” The Lab @ DC (2017). Last accessed July 24, 2023 at http://bwc.thelab.dc.gov/approach.html

Download PDF copy of the document