SIA Health Care Security Interest Group

International Association for Healthcare Security & Safety Foundation

August 2017

Document is also available via Security Industry Association

Download PDF copy of the document

Violence in the workplace continues to be a major problem in medical facilities, despite a decline in overall assault rates nationally in recent years.

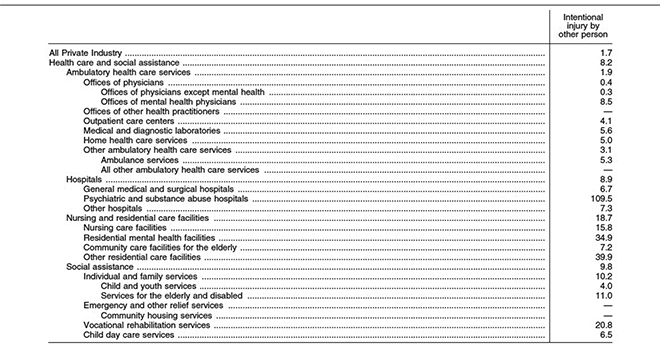

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) reports that workplace violence is four times more common in health care settings than in private industry, in general, and that about one-tenth of workplace injuries in health care settings that require days away from work result from assaults, more than triple the rate of all private sector employees. Emergency departments are a particularly high-risk area, with an April 2016 article in the New England Journal of Medicine reporting that about 80 percent of ED physicians and nurses had been assaulted during the prior year. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) illustrate the increased risk of violence that health care workers face compared to other private sector workers.

Incident Rate for Violence and Other Injuries by Private Industry in the United States per 10,000 Full-Time Workers in 2014

(Bureau of Labor Statistics, November 2015)

Note: Dash indicates data do not meet BLS publication guidelines.

Why are people in these environments so vulnerable? And what can hospitals, emergency care units and mental health facilities do to better protect staff, patients and visitors?

Stressors and Risk Factors

Formulating a strategy for addressing this problem begins with examining its root causes. Health care settings tend to be stressful environments for an array of reasons, and stress can trigger disruptive and sometimes violent, behavior.

Some of the most common stressors in medical facilities include:

- Increased wait times in hospital emergency centers

- Behavioral patients admitted to emergency departments with little or no information, and no intake facility willing or able to take the patient

- Increased use of hospitals for treatment of acutely disturbed individuals in lieu of jail or holding at police departments

Other vulnerabilities stem from the open design of many medical facilities:

- Unrestricted movement of visitors

- Spillover of gang activity from the streets

- Prevalence of firearms entering the building

And still other issues stem from financial constraints and lack of staff training:

- Budget cuts forcing leaner security staff

- Inconsistent adherence to security protocols

- Staff inability to recognize warning signs of potentially violent behavior

Regulations and Compliance

While OSHA does not currently maintain a regulation specifically related to the prevention of workplace violence in health care settings, it does require employers to “furnish to each of his employees employment and a place of employment which are free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm to his employees,” a provision known as the “general duty clause.” In recent years, OSHA has been more active in using this clause to conduct investigations and issue citations to health care facilities for issues related to workplace violence hazards.

On December 7, 2016, OSHA announced that it is “considering whether a standard is needed to protect healthcare and social assistance employees from workplace violence,” and requested comments on the subject. The public comment period closed on April 6, 2017. (OSHA has published guidelines regarding workplace violence prevention but, unlike with rules, compliance with guidelines is voluntary.)

Starting Nov. 16, 2017, health care facilities must comply with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ “Preparedness Requirements for Medicare and Medicaid Participating Providers and Suppliers.” While this rule is focused on preparedness for large-scale emergencies, such as hurricanes and disease pandemics, it requires facilities to “plan adequately for both natural and man-made disasters,” citing anthrax attacks as an example of the latter, and to conduct an “all-hazards risk assessment.”

At least nine states have laws requiring employers in the health care sector to implement workplace violence prevention policies. In 2014, California passed a law requiring health care facilities to, among other things, “adopt a workplace violence prevention plan as a part of its injury and illness prevention plan to protect health care workers and other facility personnel from aggressive and violent behavior.” The workplace violence policy must be in place by April 1, 2018, but some of the law’s mandates became effective on April 1, 2017, including a requirement that health care facilities in the state keep a record of all violent incidents.

The Joint Commission, a non-governmental accreditation and certification body, has multiple standards related to emergency management, environment of care, life safety, and related topics. For example, among its requirements are that a facility “identifies safety and security risks associated with the environment of care” and “takes action to minimize identified safety and security risks in the physical environment.” Another accreditation mandate is that, “Leaders create and maintain a culture of safety and quality throughout the hospital.” To accomplish this, they should “regularly evaluate the culture of safety and quality using valid and reliable tools,” “develop a code of conduct that defines acceptable behavior and behaviors that undermine a culture of safety,” and “create and implement a process for managing behaviors that undermine a culture of safety.”

In comments submitted to OSHA regarding its potential rule-making, The Joint Commission stated that it “welcomes the approach of a workplace violence standard, guidance, and tool kits.”

A Multi-Pronged Approach to Security

Decreasing workplace violence requires a dedicated effort on multiple fronts: people, procedures and technology.

People

From a people perspective, it starts with senior leadership accepting the fact that there is always the potential for violence in the workplace. Management must, therefore, be willing to commit adequate resources to curb it. This includes actively promoting a workplace culture that values the importance of security.

Employee education is paramount. Everyone should be informed of the purpose of security measures and prevented from circumventing electronic security devices put in place for their protection.

Security staff should be empowered to enforce rules and regulations regarding workplace violence. They should also be responsible for maintaining close relationships with local law enforcement, relying on them for a rapid response if the situation warrants it. They should record any incidents of workplace violence and report them to the appropriate departments. Those reports should be tracked to determine if there are trends and, if so, identify what can be done to address them.

Human resources should take all incidents of workplace violence seriously and deal with problems immediately – including removing staff, if necessary. HR should also oversee aftercare follow-up for any individuals who are involved in an incident.

Procedures

It is important for health care institutions to create policies, procedures and guidelines around workplace violence. Human resources, risk management, security, senior leadership and frontline staff should all provide input to ensure that these programs address the actual safety and security risks of the facility. All policies should also include aftercare follow-up for victims.

While an exhaustive list of categories of workplace violence that a facility’s policies, procedures and guidelines should address would be too long to include here, a few examples are given below.

- Domestic Violence

This should include incidents that occur at staff or patients’ homes as well as at the health care facility. The policy should direct that notifications be made to security, local police (if appropriate), human resources, and risk management, with requests for a response. It is important that all parties are notified and that information is shared rather than held by a single department.Regarding staff-on-staff incidents, ground rules should be set to ensure everyone’s safety. It must be clear that a violation of the rules by any staff member will lead to immediate termination - Workplace Violence

This encompasses incidents occurring anywhere on the grounds of the facility, whether perpetrated on staff, patients, visitors or service providers. Policies should outline the appropriate response to take and any consequences that will be levied. Policies for workplace violence must also include aftercare follow-up for any victims. - Rape and Sexual Assault

This pertains to events occurring at the facility. The policies and guidelines set for any rape or sexual assault should include immediately reporting the incident to local law enforcement and the medical facility’s police department. There should also be detailed guidelines established for collecting forensic evidence to support an investigation of the incident. - Active Shooter

In addition to having policies and procedures in place for responding to an active shooter, health care facilities should also institute mandatory annual training of security and staff in active shooter scenarios. The training should encompass prevention, mitigation, preparation, response and recovery.Security and staff should be trained to recognize potential signs of a pending threat and to conduct informal threat assessments. Is an individual more belligerent than usual? Showing up late for work? Insubordinate to supervisors? Showing signs of depression or rage? Does the person have easy access to a weapon or something that could serve as a weapon?

Technology

There are many technologies available to assist health care facilities in enhancing their safety and security. What a facility deems most important to deploy will depend on risk assessment and budgetary considerations. Some of the options include:

- Video Surveillance

IP video cameras in strategic areas can be used to monitor patients, staff and visitors. They can also be deployed in high-risk behavior rooms to enable security to watch more than one patient simultaneously. Analytics such as sound detection can further mitigate risk. - Access Control

Keycards, touchpads and/or biometrics can be used to limit access to sensitive areas. Entry privileges should be provisioned using a layered approach, becoming progressively more restrictive when moving from the property perimeter to the building perimeter to interior perimeters to the most sensitive interior areas where security risks are highest. - Body Cameras

When worn by security officers, EMTs and emergency department staff, body cameras can provide valuable evidence in criminal investigations and proceedings and civil lawsuits. - Staff Duress Alarms

Duress alarms can be installed at intake desks and nurses’ stations or carried by individuals (with real-time location systems). With preprogrammed cellphones, staff can quickly inform security of a volatile situation. - Mass Notification Systems

Mass notification systems are especially useful for broadcasting messages facilitywide in the event of an active shooter or other emergency situations.

Institutional Vigilance and Personal Vigilance

Curbing violence in a health care workplace begins with a comprehensive review of the security measures currently in place, including video surveillance and access control technology. The next step is to evaluate and review workplace violence policies to determine whether they are still timely or need to be updated. Security measures, policies and incident reports should be reviewed at least annually.

All staff – police, security personnel, social workers, psychological services, physicians, nurses and others – should be cross-trained on how to respond to workplace violence and active shooter situations and be required to attend an annual refresher course. They should also attend crisis intervention training to help them recognize warning signs of potential violence.

Employees should be trained to look at the workplace with a critical eye. Is the lighting adequate? Are there convenient escape routes? Is there a way to quickly summon assistance?

Staff needs to be proactive and attentive to behaviors that may be cause for concern. They also need to report threats from patients, coworkers and others immediately.

Other things an individual can do to help curb workplace violence include:

- Promoting respect – Fostering an attitude of respect and consideration can often defuse explosive behavior

- Eliminating potential weapons – Objects that could be used in an assault should be secured or removed

- Knowing violence response procedures – Knowing proper response techniques during violent incidents can help to minimize injuries; all staff should know how to summon assistance and move people out of danger and into safe areas

- Trusting your instincts – Staff should be trained to listen to their internal warning system if they feel something is wrong

- Working as a team – The “buddy system” should be used during a crisis; no person should be left alone

All employees have a right to work in a facility that is free from violence. By following this guidance, effectively enforcing workplace violence prevention policies, and training staff in how to recognize and react to violent situations, health care facilities can minimize risks to their patients, staff and visitors.

Resources

Occupational Safety and Health Administration, “Worker Safety in Hospitals” (web page).

The Joint Commission, “Workplace Violence Prevention Resources” (web page).

The Joint Commission, “Sentinel Event Alert,” Issue 57, March 1, 2017.

The Joint Commission, “Patient Safety Systems,” Chapter from Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals, January 2017.

The Joint Commission, “Improving Patient and Worker Safety: Opportunities for Synergy, Collaboration and Innovation,” 2012.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, et al., “Incorporating Active Shooter Incident Planning into Health Care Facility Emergency Operations Plans,” 2014.

Contact Information

The Security Industry Association Health Care Security Interest Group was created to provide resources that will enhance security in health care environments, particularly through the use of technology. The group brings together members of the electronic physical security industry, end users, law enforcement and other stakeholders to develop analyses and recommendations regarding the implementation of security solutions, the impact of emerging technologies, and the unique demands, constraints and challenges of securing health care facilities. For more information, visit www.securityindustry.org or contact Ron Hawkins, SIA’s director of industry relations, at rhawkins@securityindustry.org.

The International Association for Healthcare Security & Safety Foundation was established to foster and promote the welfare of the public through educational and scientific research and the development of health care security and safety body of knowledge. The foundation promotes and develops educational research into the maintenance and improvement of health care security and safety management and develops and conducts educational programs for the public. For more information, visit iahssf.org