IAHSS Foundation

The International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety (IAHSS) Foundation was established to foster and promote the welfare of the public through education and research and the development of a healthcare security and safety body of knowledge. The IAHSS Foundation promotes and develops research to further the maintenance and improvement of healthcare security and safety management, and it develops and conducts educational programs for the public. For more information, please visit www.iahssf.org.

The IAHSS Foundation is completely dependent on the charitable donations of individuals, corporations and organizations. Please help us continue our mission and our support of the healthcare industry and the security and safety professionals who serve institutions, staff and, most importantly, patients. To donate or to learn more about the IAHSS Foundation, please visit the website or contact Nancy Felesena at (888) 353-0990.

Thank you for your continued support.

Ronald Hawkins

Research Committee Chair

IAHSS Foundation

IAHSS Foundation Board of Directors

Bill Navejar

President

Ashley Ditta, CHPA

Treasurer

Bonnie Michelman, CHPA, CPP

Massachusetts General Hospital

Steve Nibbelink, CHPA, CA-AM

Secure Care Products

Brigid Roberson, Ed.D., CHPA

Texas Medical Center

Chad Rioux, CHPA, CPP

Motorola Solutions

Paul Greenwood, CHPA

Unity Health Toronto

Scott Hill, Ed.D., CHPA, CPP

King’s Daughters Health System

Marilyn Hollier, CHPA, CPP

Security Risk Management Consultants

Ronald Hawkins

Security Industry Association

Roy Williams III, CHPA

Download PDF copy of the document

Executive Summary

This study drew participants from hospital security teams in hospitals where security officers use body-worn cameras (BWCs) and from hospitals that have not implemented BWCs for their security officers. The goal of the research was to measure the impact of BWCs in hospital settings regarding safety, number of incidents, and attitudes toward the use of BWCs, both from those who use BWCs and those who do not. Results demonstrate the positive impacts of the cameras and the improvement of procedures in a variety of areas, including officer confidence, safety of hospital staff, better record keeping, better customer service, better training, more professional behavior from hospital and security staff, and protection against false allegations, to name a few. Specifically, the study shows that overwhelmingly the nurses and doctors do not use BWCs, most have used BWC footage to settle disputes in the hospital (78.3%), and some have used BWC footage in court (28.6%). The large majority believe BWCs are worth the cost (95.7%). The study found several significant differences in the two groups such as the hospitals that use BWCs are much more likely to have security and police officers armed with a firearm 24/7 and use other weapons beyond a firearm and Taser. The BWC group showed solid agreement that, “Our security/police officers feel safer wearing body-worn cameras.” Healthcare security leaders who do not use BWCs had many positive perceptions of their possible impact in hospital settings with some stating they would like to implement them, but others had reservations regarding their use in a hospital and doubted they would make a positive impact.

Introduction

The use of body-worn cameras (BWCs) in hospitals is not new, but there is limited research in this area. The studies that have been done show strong support for BWCs in the healthcare environment. There are reoccurring themes in the literature of how BWCs positively impact efficiency, help with training, make investigations shorter, positively impact frivolous claims, and offer protection for officers. Previous researchers have discussed how important addressing privacy rules are and stressed the importance of a good BWC policy. Interestingly there is also a theme in the literature that might argue for an increase in appropriate use of force after implementation of BWCs due to officers feeling more protection to use force as appropriate without getting into trouble. There are numerous U.S. states that mandate the use of BWCs by law enforcement officers. There is 89% support from the public in regard to requiring police officers to wear BWCs. The advocates for police body cams discuss multiple advantages the body cams bring to public safety but also the positive impact on the professionalism of law enforcement officials (Axon, n.d.).

In a review of research on BWCs, Chapman (2019) cited a study from researchers at George Mason University that lists the most commonly studied outcomes of BWCs as quality of officer-citizen interactions, “use of force by officers; attitudes about body-worn cameras; citizen satisfaction with officer encounters; perceptions of law enforcement and legitimacy; suspect compliance with officer commands; and criminal investigations and law enforcement-initiated activity” (pp. 3-4). Chapman stated how overall the research conducted on BWCs suggests there are potential benefits for law enforcement. White (2014), in a study funded by the Office of Justice Programs Diagnostic Center, also found several benefits to law enforcement. Chapman’s review shows how the earliest studies on BWCs resulted in positive interaction between police officers and citizens. There was a noted reduction in citizen complaints and some reduction in crime as well. The use of BWCs led to an increase in arrests, prosecutions, and guilty pleas. Efficiency was also an issue as the review showed the use of BWCs helped the officers resolve cases quicker and spend less time preparing paperwork, while also resulting in fewer people choosing to go to trial (Chapman, 2019).

Another 2014 study conducted by researchers at Arizona State University (as cited by Chapman, 2019) found officers with BWCs were more productive in terms of making arrests and had fewer complaints made against them as compared to officers who did not have BWCs. There was also a decrease in use of force incidents by police. This study showed how officers with BWCs were more cautious in their actions and more sensitive to the possibility they might experience pushback as their leaders reviewed their footage. It was also found in the study that officers with BWCs self-initiated with the community more than officers who did not wear cameras, which was contrary to initial concerns.

Ariel et al. (2016) that showed use of force incidents might be related to the discretion given to the officers in regard to when the BWC is activated. For example, researcher found use of force incidents went down when officers activated cameras upon arrival at the scene. However the study also showed that use of force incidents went up when officers had the discretion to determine when to activate their cameras.

A study done in Las Vegas with 400 police officers (Braga et al., 2017) found that officers with BWCs had fewer use of force reports and complaints from citizens than those without BWCs. This study also showed higher arrests and citations by officers with BWCs compared to the officers without BWCs.

Corley (2021) discussed how police departments are increasingly using BWCs to better monitor police activity in the field, reduce misconduct, and to improve fairness in policing. Corley discusses a study by the University of Chicago Crime Lab and the Council on Criminal Justice’s Task Force on Policing. Findings from this study show reduced use of police force by those who had BWCs. The study showed that complaints dropped against the police by 17% and use of force by the police decreased by nearly 10%. The study also discussed how BWCs are worth the cost with benefits such as savings due to lower use of force, reducing citizen complaints, and fewer investigations. The study states that the value of benefits versus cost with BWC implementation is 5 to 1 (Corley, 2021).

The International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety (IAHSS, 2023) has guidance for BWCs in the Healthcare Security Program Guideline 02.10 as part of their overall healthcare security industry guidelines. This guideline states how facilities implementing BWCs should develop policies with input and authorization from those in executive leadership. The document discussed how approval should require a specific policy, procedures, competencies, and equipment standards. The document also states how training programs should address several areas such as collection and sharing of audio and video recordings. The document articulates how BWCs should be treated as part of a larger multi-layered security plan.

The IAHSS (2023) Body-Worn Camera Guideline documents and defines what a BWC is, and it offers five intent statements that should be addressed by the healthcare facility. These intent statements address items of consideration by the healthcare facility to consider such as risk, liability, and other mitigation measures. The document describes how a multidisciplinary team should be used in the decision-making process and even names the departments that should be considered. The guideline provides guidance on how the facility should research privacy laws in regard to BWCs in their jurisdiction. The guideline gives specific directions on what should be included in the policy and procedures such as the primary purpose of BWCs. The guideline addresses many other items such as defining the process to inform individuals they are being recorded when required, defining when officers do not activate the BWC, handling of video, and treating recordings as protected health information (IAHSS, 2023).

Sara J. Spears authored a document for the IAHSS Foundation entitled Body-Worn Cameras (BWCS) in Healthcare (International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety Foundation [IAHSS-F], 2024). This document presents many findings that are important to those interested in implementing BWCs. The paper documents how BWCs are increasing in use, pointing to as many as 95% of police officers wearing them in large cities and counties. The document points out how the President of the United States ordered all federal law enforcement officers to begin using BWCs in May of 2022 and there are 25 states that require officers to wear BWCs. All officers use BWCs in the United Kingdom and at least 36 law enforcement agencies used them in Canada (IAHSS-F, 2024). The paper points to how proponents of BWCs believe that they are a deterrent, can decrease excessive use of force, and improve transparency and trust while improving the documentation of the incident and that BWCs are being used dramatically more in the private sector with an estimated $1 billion in growth expected from 2020 to 2025. Spears discussed how security and law enforcement in healthcare use them, but also emergency medical services, public health specifically for home health visits, and also nurses in the psychiatric/behavioral health unit, and emergency departments. The article discussed how healthcare violence has increased in the U.S. and quoted a study by the National Nurses United with 48% of the nurses reporting an increase in violence in 2022. Spears stated it is not surprising that BWCs are being considered to address concerns of increasing violence (IAHSS-F, 2024).

The IAHSS-F (2024) article addresses how there is no current regulation for BWCs, but refers to how federal and state laws apply that were actually created for audio and stationary video recording such as CCTV. The article is very comprehensive in addressing different laws, restrictions, and industry standards. This includes a discussion of one-party consent laws, but also how several states have created stricter regulations. In addition, there is also a discussion about limiting BWCs in areas where there would be an expectation of privacy. However, the expectation of privacy was diminished in several cases involving the emergency department (ED), or in other areas of the hospital. HIPAA is specifically addressed in regard to how video, photo, and audio recording is allowed for treatment, payment, and operations. The article points to multiple benefits of BWCs, including how they are small, lightweight, and durable. Other benefits in the article are that officers who had BWCs have fewer complaints, and reduction in use of force. In the IAHSS-F article, Spears cited a study in 2014 was mentioned as well with by Mulholland (2019) in which nurses wore BWCs at a high-security psychiatric hospital in the United Kingdom, resulting in a “notable” reduction in antisocial and aggressive behavior. Spears also cited a study by Ellis et al.(2019) that found BWCs reduced the seriousness of aggression and violence and showed a marked decline in the use of tranquilizing injections during restraining incidents. Other benefits mentioned by Spears were using the BWC footage for training (IAHSS-F, 2024).

The IAHSS-F (2024) review discussed other studies that did not show significant differences in use of force, or complaints. The author discussed how there are some limitations of the camera itself such as how the camera does not follow the eyes of the wearer. In addition, one should realize how the camera may see better than the human eye can in certain conditions where there is low light. The camera records in 2D, and depending on the lens, objects might seem closer than they really are, allowing a misinterpretation of the level of threat. Cost was also mentioned as a potential limitation because they require purchasing the cameras, charging stations, carriers, software, and data storage. However, items like decreased legal costs and decreased use of force incidents may help offset costs (IAHSS-F, 2024).

Two case studies in the healthcare environment were reviewed by Spears (IAHSS-F, 2024). The first case study showed clear evidence of a reduction in frivolous lawsuits. The second case study really helped executives better understand what nurses, security officers, and others deal with on a daily basis. The author takes a comprehensive approach to address many other issues such as what to record, notification of recording, protecting PHI, quality improvement, training, retention program, and release of video (IAHSS-F, 2024).

Methodology

This study used a survey design to gain insight into the experiences of hospital security/police leaders who provide BWCs for their security officers and the perceptions of hospital security/police leaders in hospitals that do not provide BWCs for their security officers. Comparisons were made between the two sets of hospitals to find differences and similarities in their beliefs regarding the benefits and concerns regarding the use of BWCs in hospitals. The survey created by the researchers began with questions drawn from a previous study on hospital security measures (Hill & Burch, 2023) and extended into questions specific to BWCs. The researchers wanted to reveal the experiences of those who use BWCs in every facet of hospital security as well as their beliefs about the impact BWCs have in their hospitals. Participants who do not use BWCs made up the control group and were asked questions to gauge their perceptions of the use of BWCs in hospitals. Both quantitative and qualitative questions were asked, including Likert scale, yes/no, and open-ended questions. Most questions were asked to both groups, sometimes with the exact wording and sometimes with a slight variation in wording (e.g., Body-worn cameras [have been/would be] very helpful in regard to customer service.).

Other questions specific to the BWC group were asked only to them and a few questions specific to the control group were asked to those participants. Participants were also asked for the number of assaults, incidents of disorderly conduct, and use of force in their hospitals monthly for six months before implementation of BWCs and for six months after implementation of BWCs. If they were in the BWC group and did not have that data and for the control group, they were asked for 12 months of data. Both surveys were reviewed by a panel of hospital security professionals and the board for the IAHSS Foundation.

Participants

There were 53 hospital security/police leaders from hospitals using BWCs who participated in this research and 57 hospital security/police leaders that do not use BWCs. All participant data were deemed valuable, so participants who did not answer some questions were kept in the data set. Respondents came from 26 states plus Australia, Canada, Puerto Rico, the United Kingdom, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Many of the participants in the BWC group were acquired through contact with Axon for a list of hospitals that use the cameras and who expressed willingness to participate in research. The researcher then contacted those hospitals. Additional participants for the BWC group were established by contacting member hospitals of the IAHSS. Participants in the control group came from a variety of groups and affiliations, including members of the IAHSS.

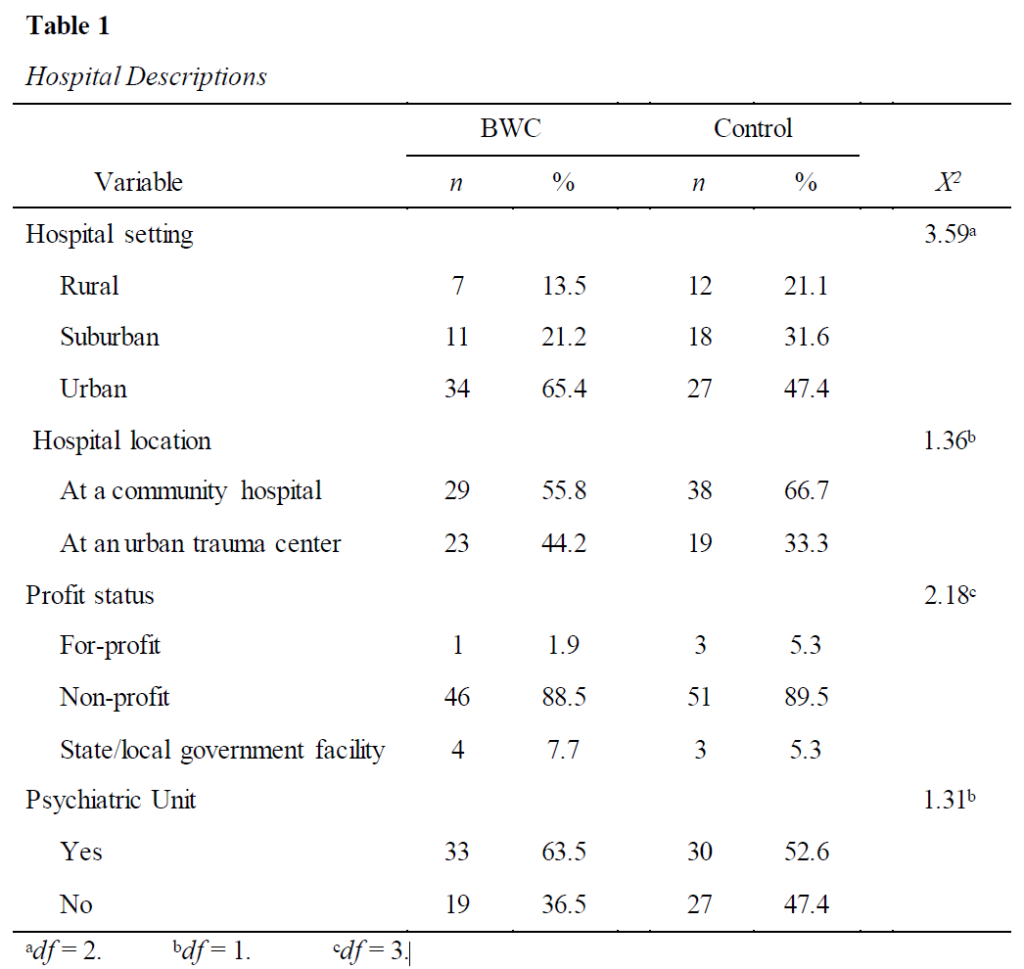

Table 1 reports descriptions of the hospitals and the comparisons through chi-square tests, which showed no differences that reached significance between the two sets of hospitals, although a gap can be seen in the percentages for urban setting, where 65.4% of BWC hospitals are located compared to 47.4% of the control hospitals. The hospitals using BWCs also have more in-patient psychiatric units (63.5% and 52.6%), although this difference was not significantly different.

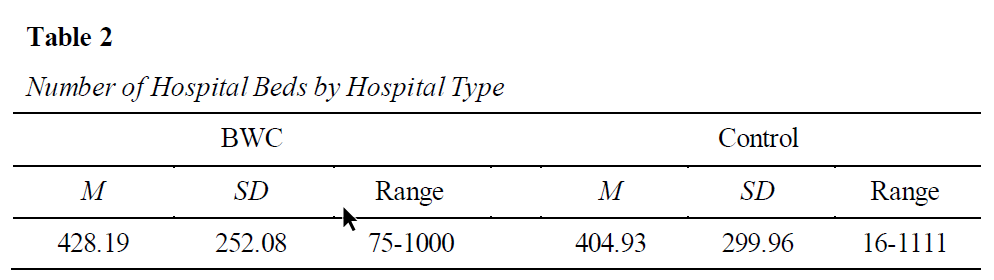

Table 2 displays the comparison of hospital size (as measured by number of beds). The two types of hospitals were very similar in terms of the number of beds in the facility when compared with an independent samples t test, t(95) = 0.40. Both groups ranged from small to very large.

Results

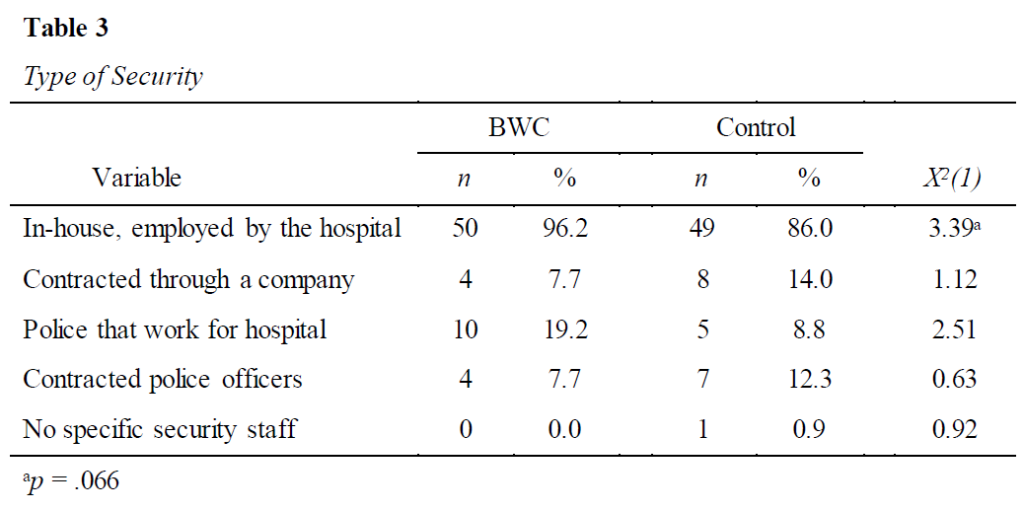

To gain an understanding of the types of security and number of officers used in these hospitals, a variety of questions were asked about security. Table 3 displays the types of security used in each type of hospital. Chi-square tests showed no significant differences in those variables although the area of in-house security was marginally significant with a higher percentage of BWC hospitals using in-house security. Another large disparity between the two groups is in the area of police who work for the hospital (19.2% for BWC vs. 8.8% for control). Overall hospitals in the BWC group employ more types of security, with 25.0% (n = 13) of the hospitals reporting they employ 2-3 types of security officers (M = 1.31, SD = 0.58), whereas 14.1% (n = 8) of the hospitals that do not use BWC employ 2-3 types of security officers (M = 1.16, SD = 0.41), t(107) = 1.57, p = .060.

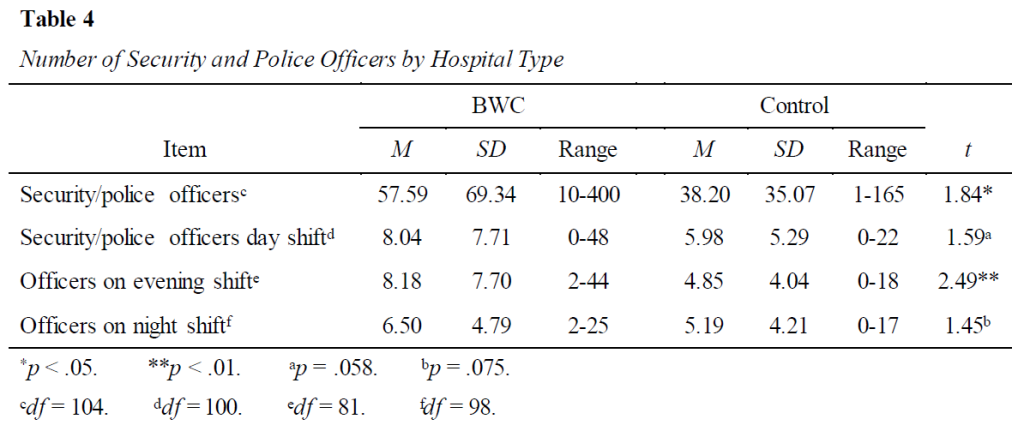

The numeric variables concerning numbers of security and police officers are reported in Table 4. T tests comparing the two groups in those four areas revealed two significant differences and two marginally significant differences in terms of security officers. Hospitals using BWCs employ significantly more security and police officers overall and have more working evening shifts. Marginally significant differences were seen in the numbers of officers during day shifts and night shifts; both showed higher numbers by hospitals with BWCs.

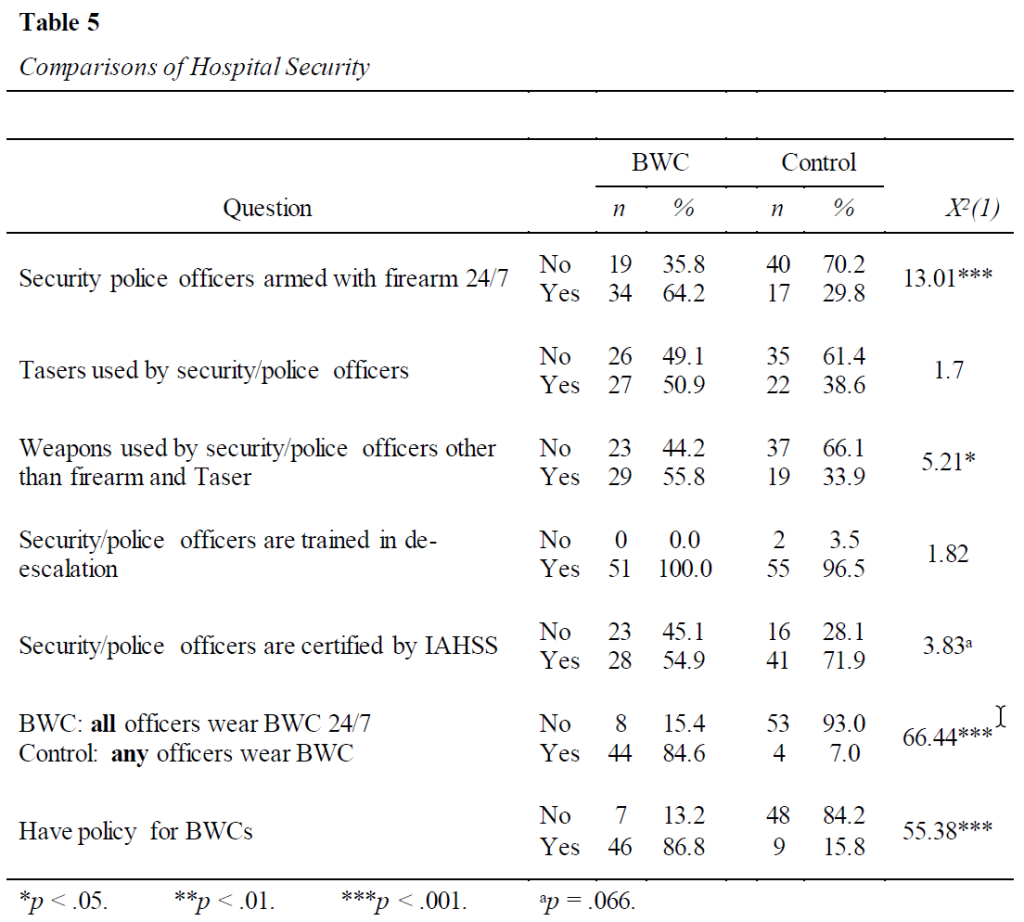

Further descriptions of hospital security were requested in order to determine the variety of hospital security included in this study and the procedures they use. The questions that were answered as yes or no are included in Table 5 along with the number and percentage of yes and no responses for both the BWC and control groups. Four of these comparisons, tested through chi-square tests, showed significant differences between the groups. Of these significant results, two dealt with officer weapons and two dealt with BWC. The significant differences show that hospitals that use BWCs are much more likely to have security and police officers armed with a firearm 24/7 and who use other weapons beyond a firearm and Taser. Hospitals that use BWCs also more consistently have a policy for BWCs and have all officers wear BWCs at all times. We also see that four participants in the control group stated they do have some officers who wear BWCs. The two groups were very similar in use of Tasers and training in de-escalation practices for security and police officers in the hospitals.

To shed more light on the responses to the question if all officers wear BWCs 24/7 (BWC group only), the BWC group was asked, “If you did not answer yes to wearing BWC’s 24/7 they were asked, “can you describe when security officers/police officers wear BWCs?” Two respondents answered no to the original question and both gave more information. One stated BWCs are worn by “those who carry Tasers, leads, and [they’re] now expanding to frontline officers.” The second person stated that two police officers in both their children and their adult hospitals wear BWC at all times, but their in-house security and other contracted security do not wear BWC.

To gain more information from the four participants in the control group who answered yes to the question, “Do any security officers wear body-worn cameras,” they were asked, “If you answered yes to the question please describe when security officers wear body-worn cameras.” All four participants who qualified for this question gave an answer and they all directly referenced police officers as the ones wearing the BWCs rather than the in-house security staff. Table 5 also shows that hospitals in the control group are more likely to have security officers who are certified by the IAHSS. This most likely resulted from reaching out to IAHSS-affiliated hospitals to request their participation in the study to garner more participation in the control group. Regarding the question in Table 5 about other weapons the officers use beyond a firearm and Taser, 15 participants in the BWC group said they use OC/pepper spray and 14 participants stated they use batons. Responses from the control group included a baton (n = 10), OC/pepper spray (n = 8), handcuffs (i = 4), and OC/pepper spray (n = 2).

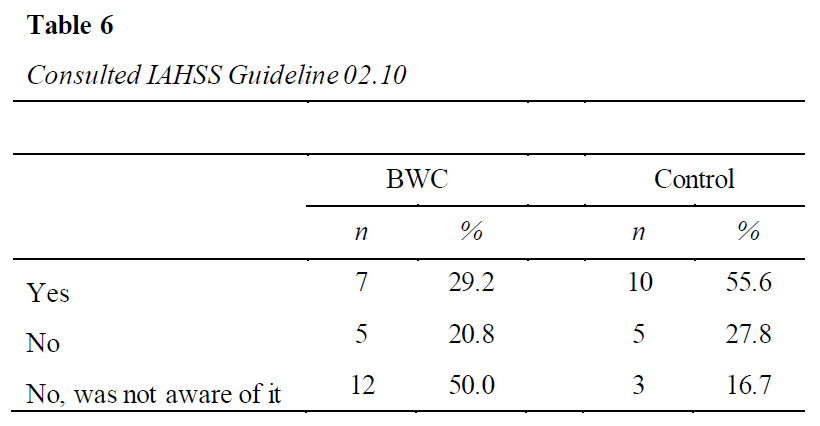

Participants in the BWC group were asked if they consulted IAHSS Guideline 02.10 Body-Worn Cameras in the Healthcare Security Program before BWC implementation while participants in the control group were asked if they consulted the guideline to get information regarding BWCs. As seen in Table 6, hospital hospital security/police leaders in the control group had consulted the IAHSS guideline more so than BWC hospital administrators, who most often stated they were not aware of this guideline, X2(2, N = 42) = 5.18, p = .075.

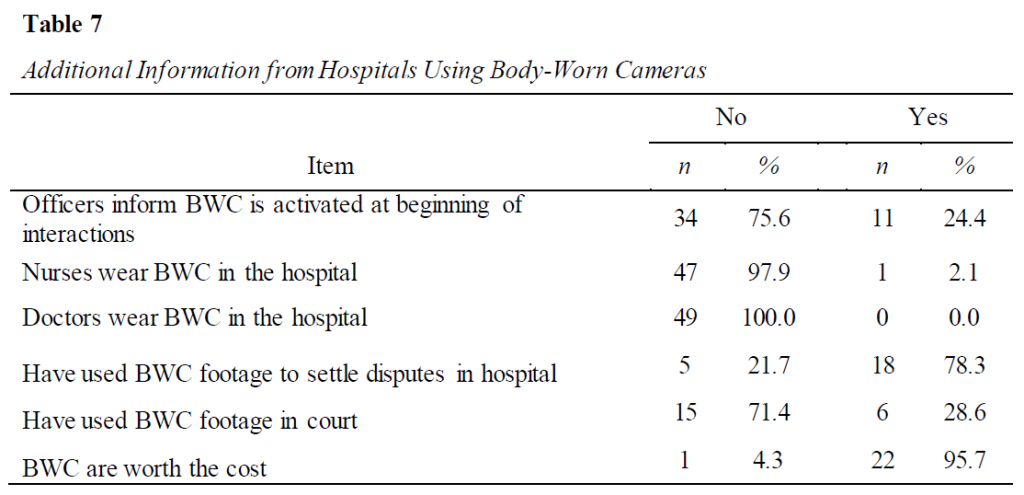

The next selection of items appeared only on the survey for participants who use BWCs in their hospitals. These six questions asked about procedures used with BWCs, how the footage has been used, and if they believe BWCs are worth the cost. Table 7 shows that overwhelmingly the nurses and doctors do not use BWCs, most have used BWC footage to settle disputes in the hospital (78.3%), and some have used BWC footage in court (28.6%). The large majority believe BWCs are worth the cost (95.7%).

Qualitative findings shed more light on these results. Regarding BWCs being worth the cost, those who use them were asked to give more information on these beliefs and 12 participants stated it was worth the cost to have the true accurate story of what occurred, but also mentioned how helpful they were in regard to protecting against litigation and accusations. Regarding how they have used BWC footage to settle disputes in the hospital, 14 participants stated BWC footage helped the security staff clear up disputes about accusations toward officers related to inappropriate action, inaccurate statements, excessive force, inappropriate behavior, and officer conduct. Two other participants actually used BWC in court as evidence in their cases, and the other was when a security officer stopped an auto theft and they used the footage in court.

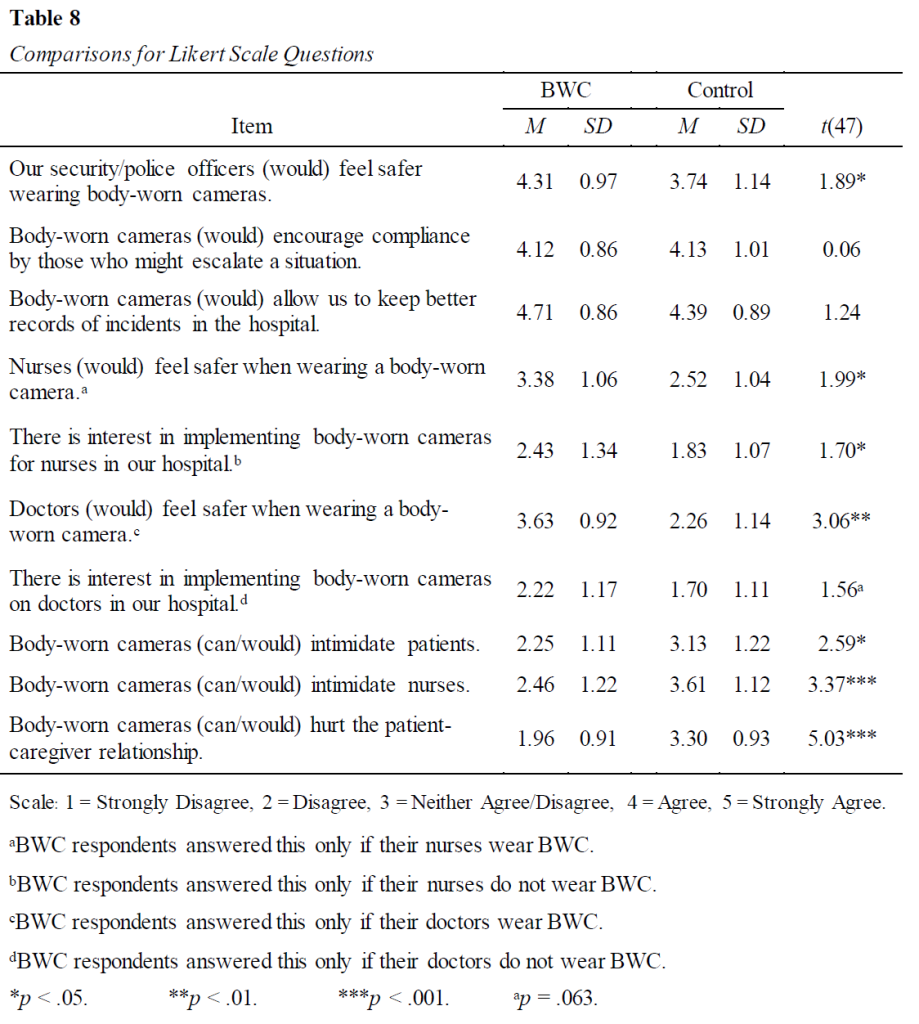

Respondents from hospitals that use BWC were asked questions regarding their experiences with BWC and respondents in the control group were asked corresponding questions about their beliefs regarding those same issues with BWC with a slight difference in wording. Table 8 shows these Likert scale questions; words in parentheses show the wording for the control group. Table 8 also shows the mean responses for each group. Of these 10 items, seven showed significant differences when compared using independent samples t tests and one item was very close to reaching significance. In each of these cases, the means show those who have used BWC preferred BWC more than the control group.

Of note from Table 8 is how high the means are for both groups for the items, “Our security/police officers (would) feel safer wearing body-worn cameras,” “Body-worn cameras (would) encourage compliance by those who might escalate a situation,” and “Body-worn cameras (would) allow us to keep better records of incidents in the hospital.” For these three items both groups answered with agreement and only one of these showed a significant difference between the groups, meaning that both groups were very similar in the strength of their agreement.

The item “Nurses (would) feel safer when wearing a body-worn camera” was supposed to be answered by the BWC group only if the nurses wear BWC, but eight participants responded to that item, most likely by mistake, since only one person stated that nurses in their hospital wear BWCs. The responses were in agreement of nurses feeling safer when wearing a BWC, but when asked if they intend to implement BWC for nurses if they did not already use them, both groups respondent with disagreement. Similar items regarding doctors were asked with similar results. Although the item “Doctors (would) feel safer when wearing a body-worn camera” was only supposed to be answered if doctors in the hospital use BWC, and previously all respondents stated that doctors in their hospitals do not wear BWC, the same eight participants answered this question with agreement. When asked if there was interest in implementing BWC for doctors, both groups answered with disagreement. Still, for each of these responses the means for the BWC group are higher than the means for the control group.

The results in Table 8 demonstrate that hospitals that do not use BWCs have concerns over the effects of BWCs on patients, nurses, and the patient-caregiver relationship. There were significant differences in three areas with the control participants answering in agreement that BWCs could intimidate patients and nurses and could hurt the patient-caregiver relationship. Participants from hospitals that use BWCs answered on the disagree end of the scale in all three of these areas. This appears to demonstrate that these three areas are concerns for hospital security/police leaders who do not have experience with BWCs, but healthcare security/police leaders with experience with BWCs have not experienced these negative effects.

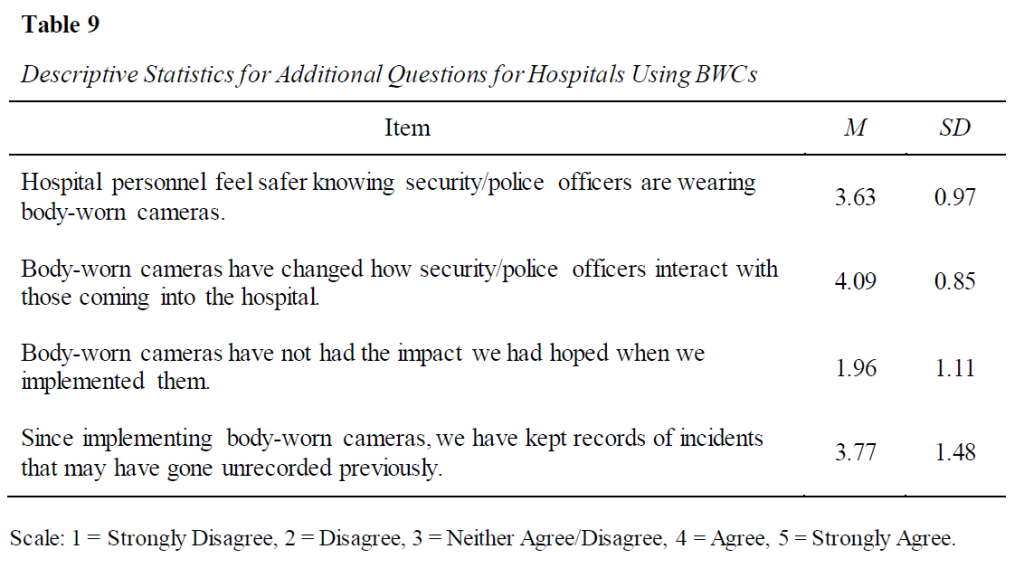

Four additional Likert scale questions that dealt with their experiences using BWCs were asked of the respondents who use BWCs. All of the means shown in Table 9 demonstrate the participants’ preference for using BWCs, the advantages of the BWCs, and that BWCs have had the impact they had hoped.

Using the same scale, the control group was asked if there was interest in implementing BWCs on security officers in their hospitals. The responses spanned the whole range of options from strongly agree to strongly disagree with the majority answering with an affirmative response (67%, n = 16) and a mean of 3.75 (SD = 1.33).

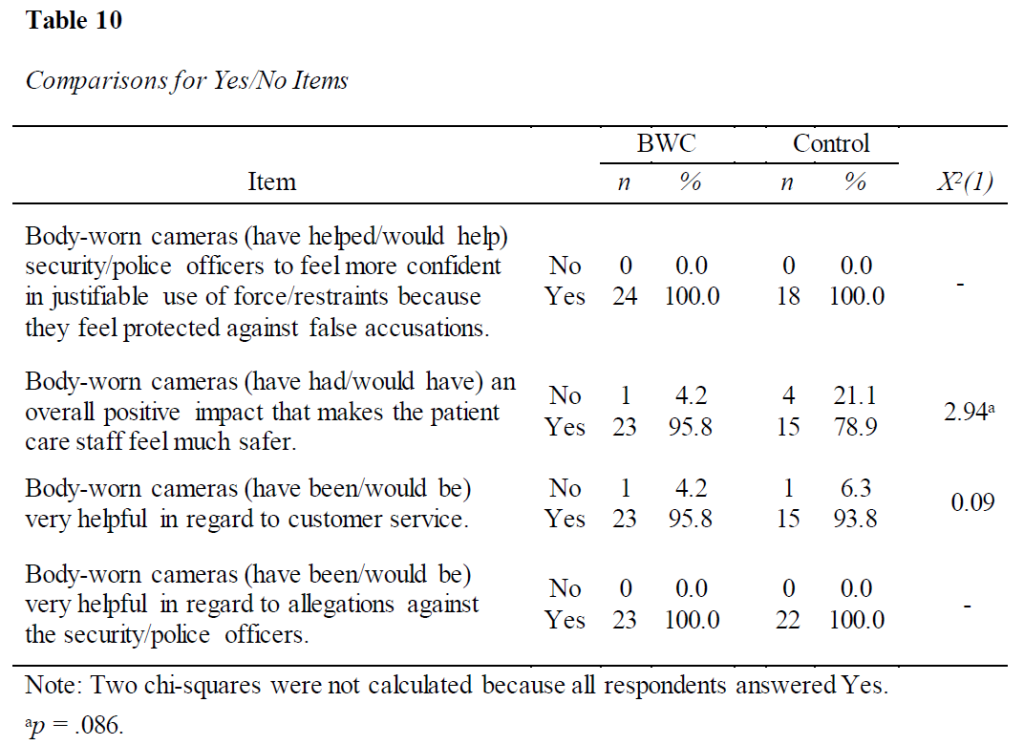

A selection of questions with yes/no responses was included on the survey to ask about respondents’ beliefs about the benefits of body-worn cameras. Respondents with BWC in their hospitals responded based on their experiences and respondents who do not have BWC in the hospitals responded based on their beliefs about the usefulness of BWC. Table 10 displays these questions and the slight differences in wording for each of the groups, as well as the numeric results for their responses. All participants answered Yes to two of the four questions, showing a unanimous belief that BWCs help officers feel more confident in justifiable use of force and restraints and protect against false allegations against the officers. There were no statistical differences between the two groups; however one question that came close to significance is the question about an overall positive impact that makes the patient care staff feel safer, in which the large majority in both groups answered affirmatively, with only one person in the BWC group answering no.

As seen in Table 10, the great majority of participants in both groups believe BWCs are helpful for customer service. Additionally, participants who use BWCs explained specifically how BWCs reduce escalation, there are fewer confrontations, officers and staff are more aware of their behavior, interactions are more professional and courteous (officers, nurses, and clinical staff), complaints are more readily dismissed, and some people do not even realize they are there because the camera is part of the uniform.

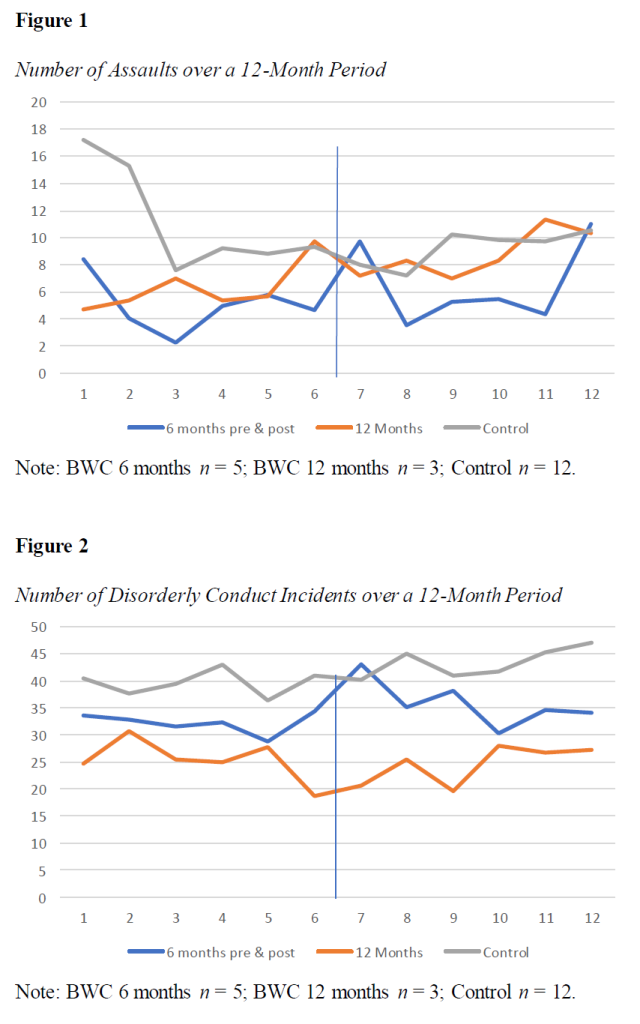

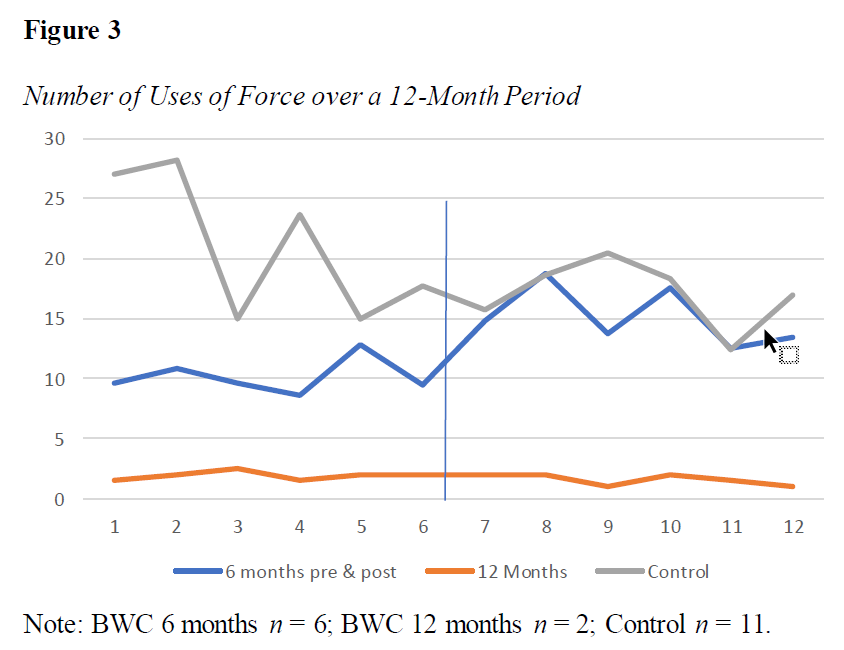

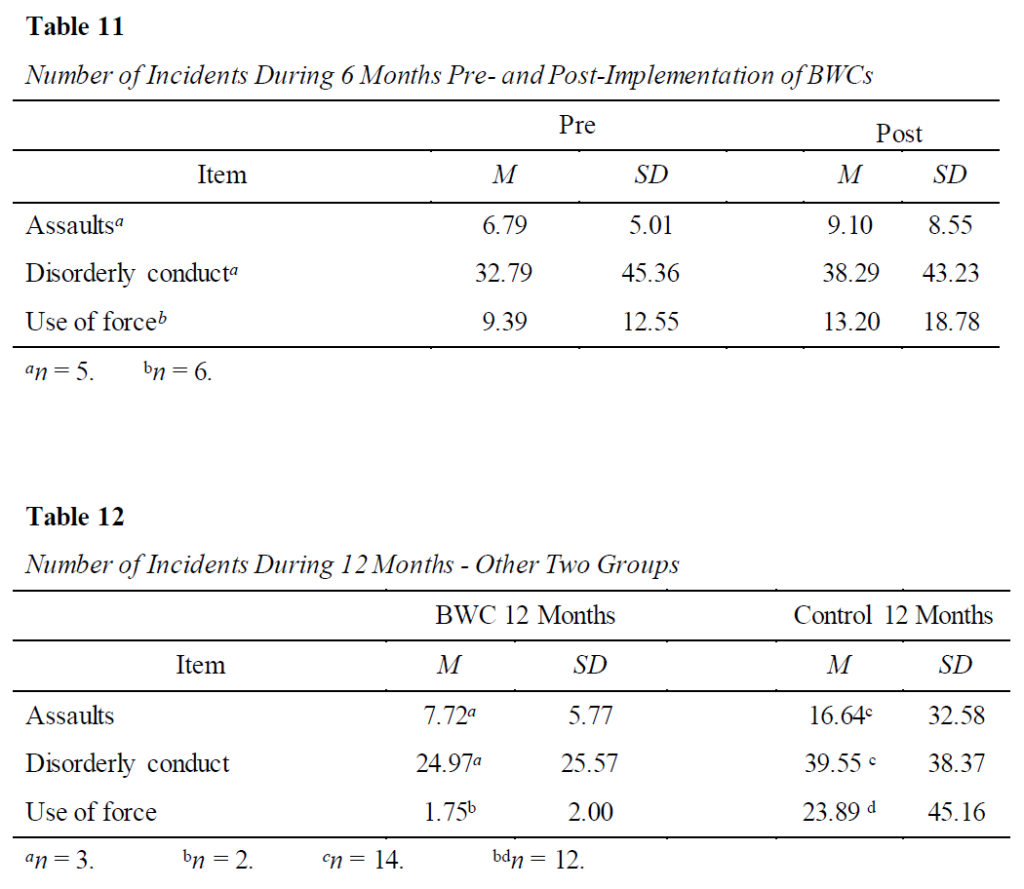

In addition to the questions about experiences and beliefs regarding BWCs, the survey asked for 12 months of data for number of incidents of assaults, disorderly conduct, and use of force by security or police officers. BWC participants were given two options for the 12 months of data; the preferred method was six months of data before and after implementation of BWCs but if they did not have that, participants had the option to provide 12 months of consecutive post-implementation data from the past 15 months. Participants in the control group were asked to give 12 months of data from the last year. Unfortunately, only five participants in the BWC group gave the 6-month pre- and post-data for assaults and disorderly conduct and six gave the data for use of force. Only three participants gave 12 months of data post-implementation. In the control group, 12 gave data for assaults and disorderly conduct and 11 for use of force. This makes any comparisons and generalizations regarding these types of incidents unviable. These data are presented in Figures 1, 2, and 3 for informational purposes only. The line in each graph represents the point at which BWCs were implemented.

To see if these smaller groups differed in hospital characteristics, additional descriptive statistics were run. The groups were very similar in that all (BWC) or most (control) had a psychiatric unit, all security officers were trained on de-escalation techniques, most used in-house security, all (BWC) or most (control) did not use contracted security, 67-85% did not use police officers, and most (BWC) or all (control) did not use contracted police. BWC hospitals were much higher in the areas of having armed officers 24/7 (89% to 43%), officers using Tasers (67% to 29%), and officers using other weapons (67% to 31%). The control group was higher in IAHSS certification (93% to 44%).

The data that were given as six months pre-implementation and six months post-implementation were aggregated into means for pre- and post-implementation in the areas of assaults, disorderly conduct, and use of force. As can be seen in Table 11, the numbers in each area increased after the implementation of BWCs. Statistical comparisons were not possible with such small numbers of participant responses in these categories. The 12 months of aggregated data in each area for each of the other grouping for these data (BWC group with 12 months of post-implementation data and the control group with 12 months of data) are reported in Table 12.

All participants were asked about the impact of BWCs on the use of force by security and police officers. The BWC group had 15 positive comments in regard to their perception of the impact of BWC on use of force by their staff. =Participants articulated BWCs have a great impact, are a great tool, said the impact is extremely positive, they serve as a great asset, are a great evidence tool that is accurate, and described BWCs as an excellent training tool. Four participants stated the BWC reduces use of force incidents. Interestingly four participants pointed out BWCs provide a safer environment as they help officers use force appropriately more often because they know they have more protection. One person noted their use of force incidents increased after implementing BWCs because officers respond more quickly and are more confident engaging because they feel protected by the BWC. The control group had eight participants who stated the BWCs would be good for accountability and transparency and would reduce false complaints. Seven participants from the control group believed use of force incidents would go unchanged if BWC were implemented. Four participants in the control group stated they believed less force would be used because of fear of being on video.

Both the BWC group and control group were asked, “From your perspective, what is the impact on violence by having BWC in your hospital?” The BWC group had seven participants specifically mention the importance of BWC in obtaining accurate information as to what happened and how they assist in investigations. Six participants stated the BWC helped de-escalate or provide a deterrent. There were also six participants who that mentioned the BWC helped boost a professional and appropriate response. Five responses mentioned how BWC provide protection against litigation. The control group had some similar but also some different perspectives. Six participants stated BWCs would help de-escalate or provide a deterrent. Four participants in the control group stated that BWCs would help provide protection against litigation and four participants mentioned how BWCs would help provide accuracy of what occurred and assist in the investigation. However, five participants in the control group believed there would be no difference or very minimal difference on violence by having BWCs.

All participants were asked about the impact on BWC on training and development of security/police officers or other staff. Of the responses from those who use BWCs, 10 participants stated the BWCs have positively impacted the training and development of security/police staff. Participants mentioned a big return on investment, how BWCs have a huge impact, and how they are phenomenal and very beneficial. The control group had 10 participants who mentioned that from their perspective the BWCs would be a great tool for training and development, would help officers improve their de-escalation techniques, and have a positive impact on training. Four participants from the control group stated they did not believe BWCs would have a positive impact on training and development. Their reasons were staff would not like being monitored, BWCs would be challenging to implement, and they would require more resources.

Because legal liability is an important reason hospitals adopt BWCs, all participants were asked for their perceptions of the impact of BWCs in this area. Twenty participants from the BWC group described a positive impact on legal liability. The comments from the participants were that lawsuits have been dropped after reviewing video, evidence is available that supports the hospital/officer, protects the hospital/officer from litigation, can quickly validate facts, transparency is increased, and BWCs offer protection against false claims. The control group had nine participants who articulated their beliefs that BWCs would have a positive impact on legal liability. Their comments included staff would be better protected, they would protect the hospital/officer, support legal defense, help with false claims, and would have a great impact on overall liability. The control group had five participants share concerns about privacy, liability of the BWCs, HIPAA violations, or they are worried about BWCs opening them up to litigation.

BWCs can be used as a training tool, so the hospital security/police leaders who use BWCs were asked about this area. There were 19 positive comments regarding how the BWCs had been a helpful training tool, including that BWCs allow officers to critique themselves to perform better in the future and how the BWCs have been the greatest tool they have implemented. Participants also mentioned how they use the BWCs to train new officers, but also for in-service for veteran officers. Participants described how some videos are extra helpful and they mark them as coaching videos for others to learn from. Participants also articulated how BWC footage helps officers to understand what does and does not work in regard to spacing and physical response to physically aggressive persons. Participants mentioned how the BWCs are helpful for them to learn from to make improvements going forward, and how to avoid dangerous situations in the future.

When the BWC group was asked about the key to successfully implementing BWC in the healthcare environment six participants articulated that staff buy-in is important from the security and police but also from the clinical staff. It was mentioned multiple times how BWCs can help protect staff from false accusations. Clear communication was also mentioned by six participants in regard to what to expect, benefits, and providing reassurances for successful implementation. Policy and training were mentioned four times by participants as being keys to successful implementation. Obtaining buy-in by senior leaders and Legal was also mentioned specifically four times as being important.

Hospital security/police leaders who have BWCs discussed the pushback from the security staff, the Legal Department, or others in regard to implementation of BWC. Ten participants stated they did not have any pushback from anyone. Six participants stated initially security staff or clinical staff had concerns about being watched or terminated, but concerns were alleviated quickly after implementation. Three participants mentioned pushback from Legal in regard to HIPAA or privacy concerns initially and one person said the journey to BWC deployment was intense and at times frustrating, but well worth it.

Regarding advice they would give other hospitals that are considering implementing BWC for security/police officers, 11 simply stated they should implement BWCs. There were comments like they are gold, do it, strongly recommend BWCs, they are a great valuable tool, a tool for better accuracy, so glad they have them, and make the purchase. Eight participants stated it is important to explain why you want them. They offered reasons such as return of investment (ROI), protection against false accusations, protections against civil litigation, and they help with misunderstandings. Finally, seven participants stressed the importance of focusing on policy and training of policy when considering implementation.

The control group had two open-ended questions about why they do not use BWCs and if there have been discussions in their hospitals about BWCs. Five people said there have been no discussions while 10 people said they have been in discussion about them, ranging from low level discussions to multiple discussions, others had comments such as there is great interest but no funding, and some were in the process of purchasing. The top reason for not using the cameras was the cost, including start up cost and personnel. There were six mentions of HIPAA, two each for legal and video storage, and one mentioned privacy. Interestingly, one of those people sounded like those concerns were unfounded by saying, “HIPAA misunderstandings … misunderstanding of consent laws.”

Lastly, both groups were asked for any other thoughts they had concerning BWCs and their impact on violence and the healthcare security/police program. There were seven participants from the BWC group who made further positive comments about BWCs. Comments were BWCs have been a great tool, I highly recommend BWCs, BWCs are a great addition to security, BWCs promote transparency, BWCs safeguards security staff and other people, and BWCs capture threats on video. There were also nine positive comments from the control group, including BWCs are a must today in healthcare, from their perspective BWCs deter complaints, BWCs helps with limiting time spent on investigations, and serve as a great deterrent. The control group had other comments such as how they are currently advocating to get BWCs in their department, how BWCs protect staff from false allegations and litigation, and how BWCs can help create an overall safer and more secure healthcare environment.

Discussion

Although the two sets of hospitals are similar in size (as seen in Table 2), descriptions (Table 1), and the types of security they employ (Table 3), there were some disparities in those areas. Notably, more of the hospitals using BWCs are located in urban settings and are in an urban trauma center. They are more likely to have a psychiatric unit and to have police who work for the hospital at a higher rate than hospitals that do not use BWCs.

The two types of hospitals were significantly different in several characteristics, with hospitals that use BWCs utilizing more security and police officers overall and on the evening shift. They also utilize more officers on the day shift and night shift and employ more types of security. Officers in hospitals with BWCs carry firearms at a much higher rate, as well as using other weapons beyond a firearm and Taser. Regarding security officers certified by the IAHSS, the control group had significantly more, most likely because the control group was partially made up of hospital security/police leaders who were affiliated with the IAHSS. This corresponds with the finding that hospital security/police leaders in the control group had consulted the IAHSS guideline regarding BWCs at a much higher rate than the hospital security/police leaders who use BWCs. The two sets of hospitals used Tasers and were trained in de-escalation techniques at similar rates.

Hospital security/police leaders from hospitals using BWCs affirmed the benefits of them in every question they answered. There were no items in which the aggregated data for the BWC group showed they were disappointed with the use of BWCs. An overwhelming majority (96%) of participants who use BWCs believe they are worth the cost for a variety of reasons, including protection against litigation and false accusations. Participants confirmed BWCs have had the impact they had hoped for when deciding to implement them. Over 78% of them have used BWC footage to settle disputes in the hospital and 29% have used BWC footage in court. Hospital personnel feel safer knowing their security and police officers are wearing BWCs. Disputes that have been settled using BWC footage include accusations toward officers related to inappropriate action, inaccurate statements, excessive force, inappropriate behavior, and officer conduct. BWC footage has been used in court as evidence in multiple cases, including theft of an automobile outside the hospital.

There were also areas where hospital security/police leaders in hospitals that do not use BWCs responded positively about the usefulness and benefits of BWCs and the majority of them stated there was interest in implanting them in their hospitals (67%). There was unanimous agreement in both groups that BWCs help security and police officers feel more confident in justifiable use of force and restraints because they feel protected against false accusations and that they are helpful in regard to allegations against the officers in general. Both sets of participants gave very high ratings for questions about security and police officers feeling safer, the patient care staff feeling safer, that they are helpful in regard to customer service, they encourage compliance, and they help staff keep better records of incidents in the hospital.

These results shed more light on the increase in the number of assaults, disorderly conduct, and use of force incidents seen in Table 11. Hospital security/police leaders believe those who might escalate a situation are more likely to comply when they know a BWC is being used, which would result in fewer incidents in these three areas; however, BWCs also allow them to keep better records of the incidents that do occur, whereas some previously went undocumented, which explains why these numbers increased. These findings also concur with the results of our previous study on hospital security measures (Hill & Burch, 2023), which showed that hospitals that use more types of security measures record higher numbers of these types of incidents for a variety of reasons, including that they have more incidents and therefore need the additional security measures, and the presence of security officers and other measures like cameras allow for better documentation of incidents as they occur. Of course, the increases seen in this study are based on a very small number of hospitals that provided data for assaults, disorderly conduct, and use of force, but it stands to reason that recorded incidents should increase when there is documentation and video evidence of the incidents as they occur. Also, because the officers feel better protected and safer using justifiable use of force or taking appropriate action when necessary, the number of documented use of force incidents would increase. In turn, this leads to some of the previously discussed findings that show nurses, doctors, and staff feel safer when BWCs are in use.

There were also areas that showed concern about the effects of the presence of BWCs by participants who do not use them, but were rated positively by those who do use them. Hospital security/police leaders with experience with BWCs do not believe BWCs intimidate patients or nurses, or that they hurt the patient-caregiver relationship. In contrast, hospital security/police leaders without experience with BWCs believe BWCs would intimidate patients and nurses and would hurt the patient-caregiver relationship. These beliefs appear to be unfounded based on the experience of the BWC group.

Some of the qualitative responses also showed mixed beliefs about the effects of BWCs by the control group while those who use BWCs shared only positive impacts. These can be seen in questions about the impact on violence, impact on training and development, and impact on legal liability. In each of these areas respondents in the BWC group shared their experiences of how BWCs have helped to de-escalate situations, improve professionalism from everyone involved, improve training procedures, and provide evidence to refute false allegations. For the most part, the responses from the control group also assumed positive outcomes, but there were four to five participants who expressed skepticism that BWCs would have any impact in those areas or that they would negatively impact privacy and litigation.

Participants who use BWCs agreed that nurses and doctors would both feel safer if they wore BWCs, but participants who do not use BWCs disagreed with these statements. In contrast, both groups stated there is not interest in their hospitals for implementing BWCs on nurses or doctors, with the control group stating that more strongly.

In conclusion, there are reasons the BWC group chose to use BWCs, either because of incidents taking place in their hospitals or because hospital security/police leaders believed they would have a positive impact. The fact that hospitals with BWCs also have more officers who carry firearms and other weapons, along with the increased presence of security, alludes to the presence of more disputes and situations in which BWCs can be very helpful. Hospital security/police leaders described the experiences they and their staff have had while using BWCs in their hospital and expressed overwhelming satisfaction with the outcomes. These data provide strong evidence of the impact of BWCs in the settings in which they are used by security and police officers, both for the officers who wear them and the doctors, nurses, other staff in the hospitals, and visitors by creating a safer environment. When all those involved know they are being recorded, they are much more likely to behave in a professional and respectful manner.

References

Ariel, B., Sutherland, A., Henstock, D., Young, J., Drover, P., Sykes, J., Megicks, S., & Henderson, R. (2016). Report: Increases in police use of force in the presence of body-worn cameras are driven by officer discretion: A protocol-based subgroup analysis of ten randomized experiments. Journal of Experimental Criminology 12(3), 453-463.

Axon (n.d.). The pros and cons of police body cams. Retrieved April 26, 2024 from https://www.axon.com/resources/police-body-cam

Braga, A., Coldren, J. R., Sousa, W., Rodriguez, D., & Alper, O. (2017). The benefits of body-worn cameras: New findings from a randomized controlled trial at the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice.

Chapman B. (2019, January). Body-worn cameras: What the evidence tells us. NIJ Journal ,280. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/252035.pdf

Corley, C. (2021, April 26). Study: Body-worn camera research shows drop in police use of force. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2021/04/26/982391187/study-body-worn-camera-research-shows-drop-in-police-use-of-force

Ellis, T., Shurmer, D., Badham-May, S., & Ellis-Nee, C. (2019). The use of body worn video cameras on mental health wards: Results and implications from a pilot study. Mental Health and Family Medicine, 15(1), 859-868.

Hill, S., & Burch, M. (2023). Effective controls on emergency department violence. International

Association for Healthcare Security and Safety. https://iahssf.org/assets/2023-Effective-Controls-on-Emergency-Department-Violence.pdf

International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety (IAHSS). (2023). Industry guidelines. https://www.iahss.org/global_engine/download.aspx?fileid=F57188CF-4EC3-44E4-913F-FB7467265D0D&ext=pdf

International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety Foundation (IAHSS-F). (2024). Body-worn cameras in healthcare. Evidence-Based Healthcare Research Series. https://iahssf.org/assets/Whitepaper-Body-Worn-Cameras-in-Healthcare.pdf

Mulholland, H. (2019, May 1). Can body cameras protect NHS staff and patients from violence? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/may/01/body-cameras-protect-hospital-staff-patients-violence-mental-health-wards

White, M. D. (2014). Police officer body-worn cameras: Assessing the evidence. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.